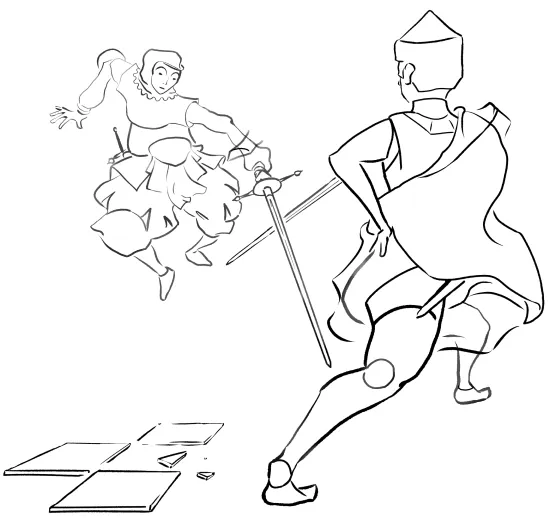

Veney is a chesslike hyper-rock-paper scissors game of abstract strategy, for two players, designed to invoke the mechanics and spirit of fencing.

Contents

OVERVIEW

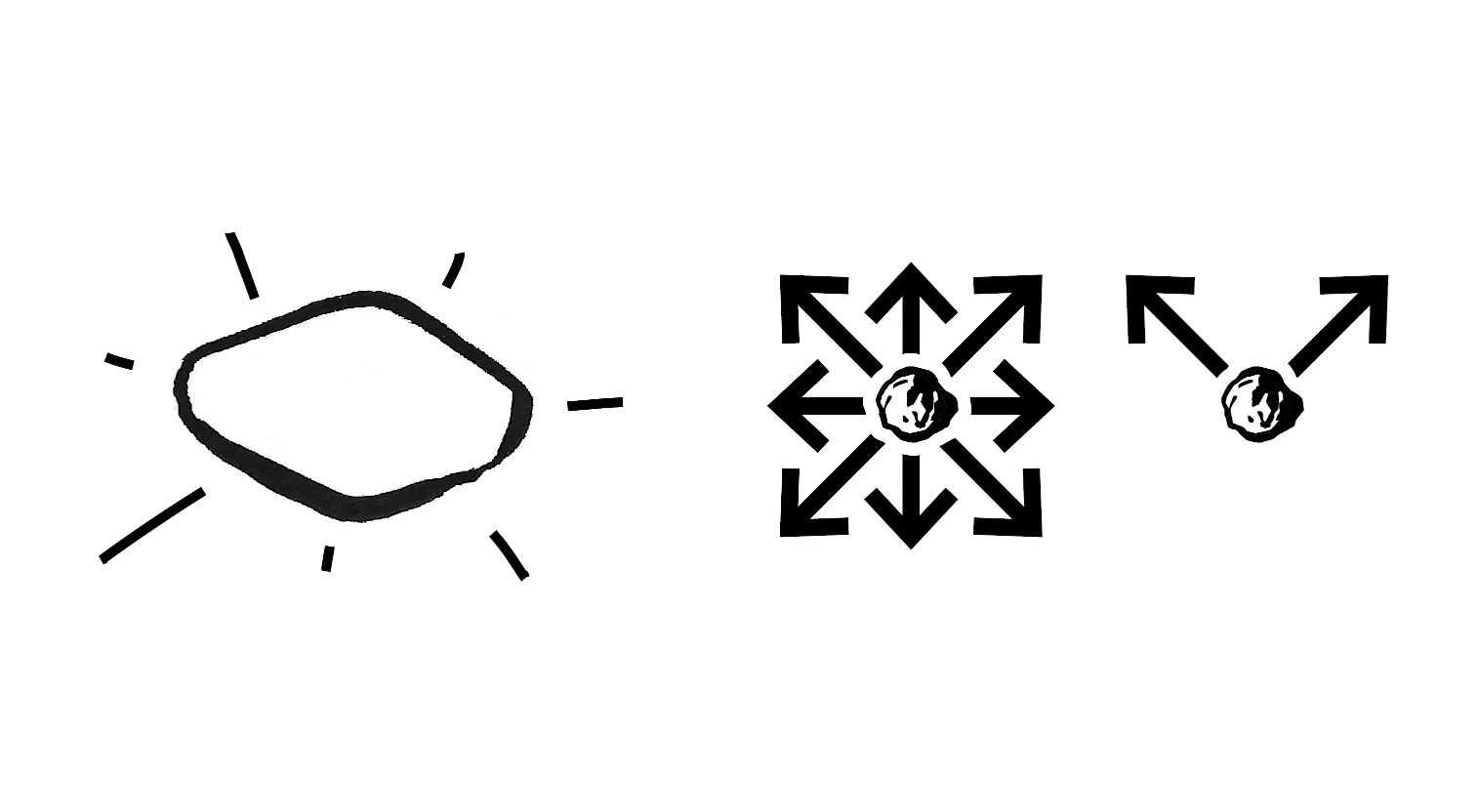

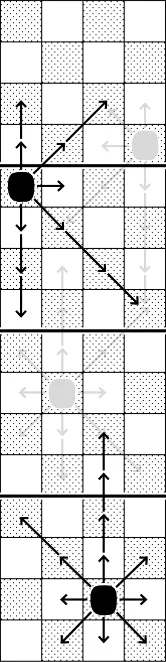

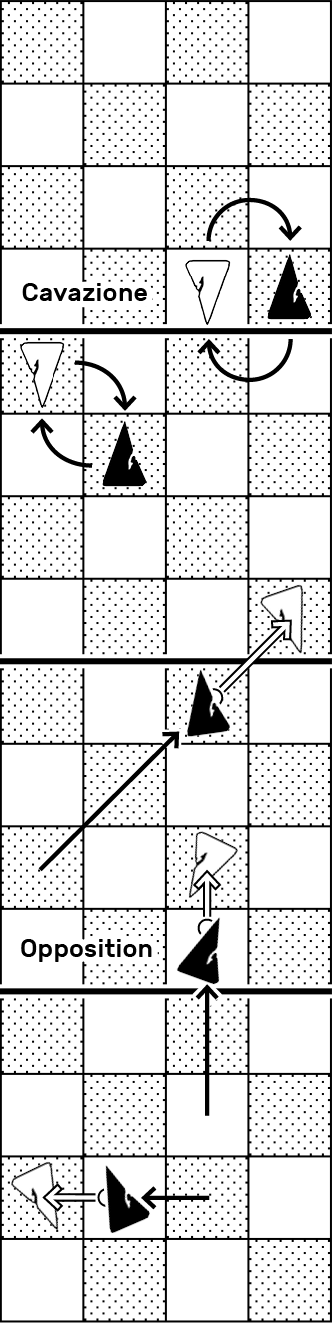

Fig.A Summary: The Pieces (In Brief)

2.0.I Introduction & Comparison to Chess

2.0.II Three Precepts of Spirit

2.0.III Playing with Sand

2.0.IV Overall Play & Goal

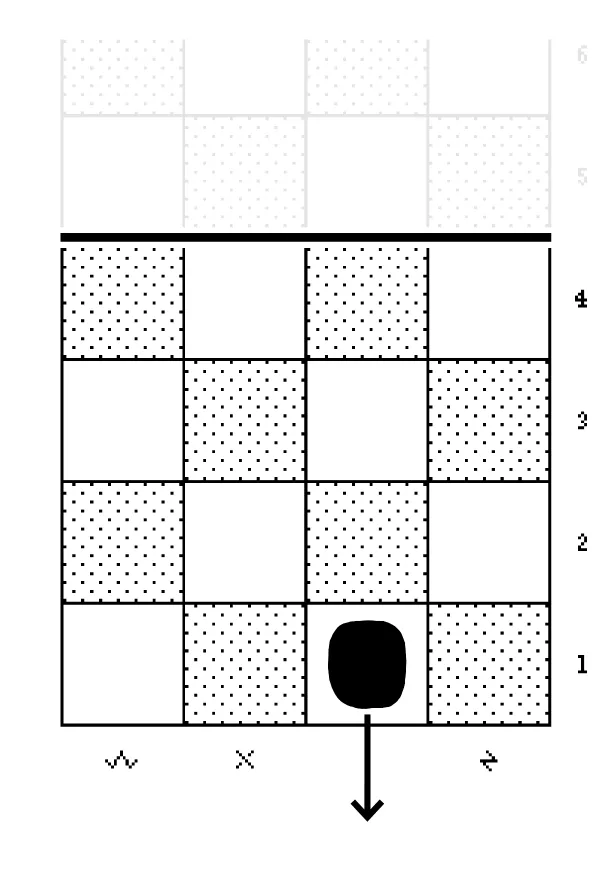

2.0.V The Board

2.0.VI Types of Pieces

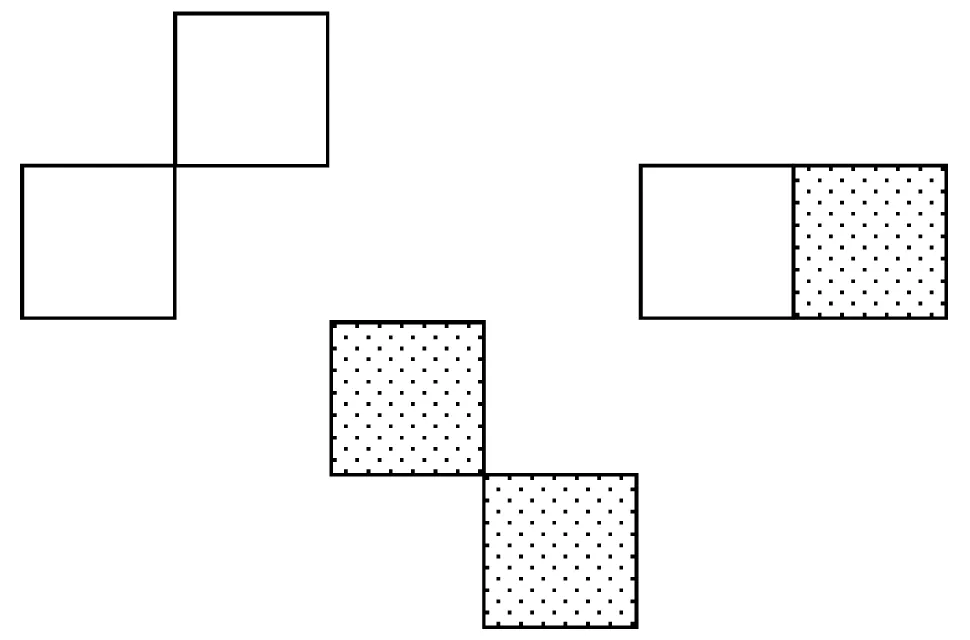

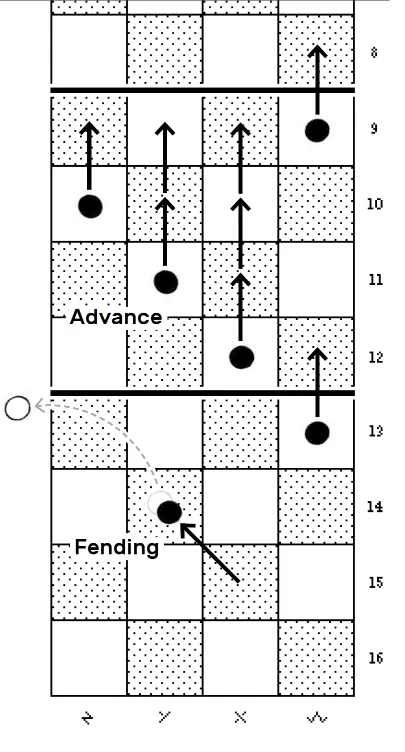

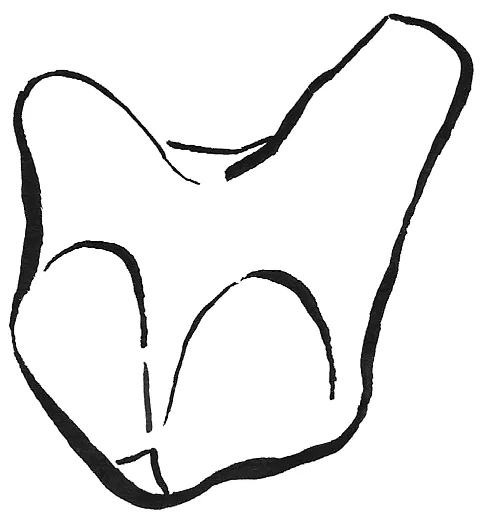

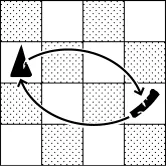

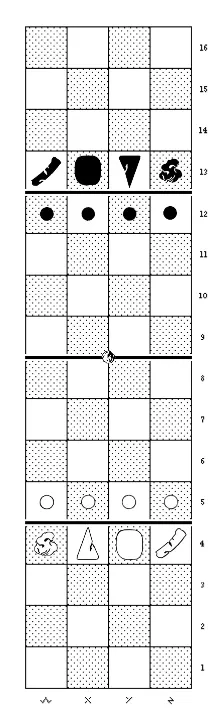

Fig.B Diagram: Types of Pieces

2.0.VII Terminology: Take or Fend?

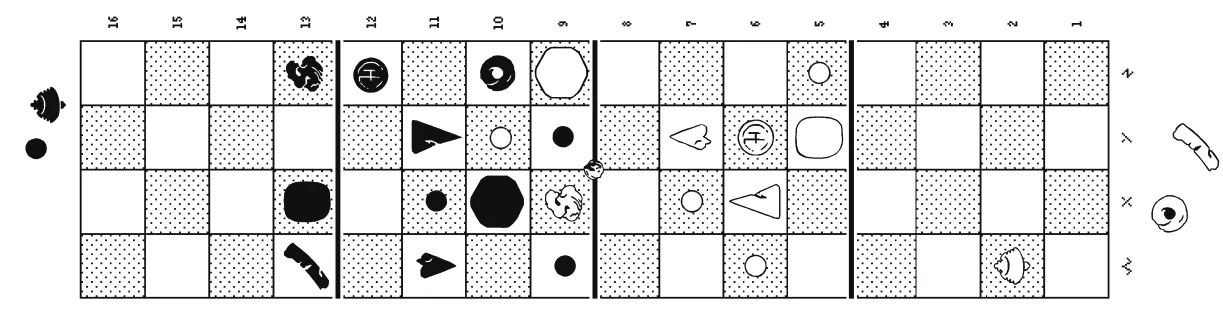

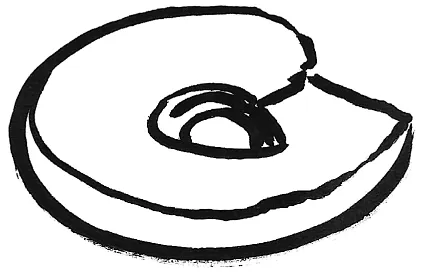

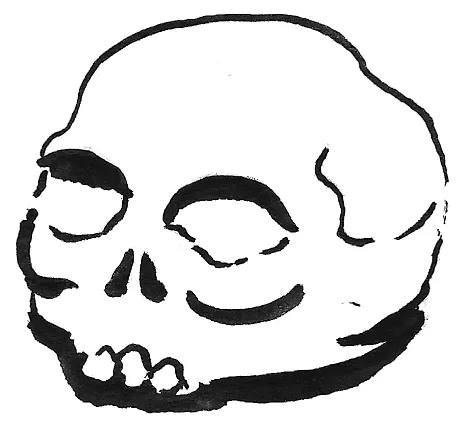

Fig.C Summary: Taking & Fending

RULES

2.0.01 The Pieces, Movements & Specials

2.0.02 Self

2.0.03 Sword

2.0.04 Engagement (pawn)

2.0.05 The Free Engagement

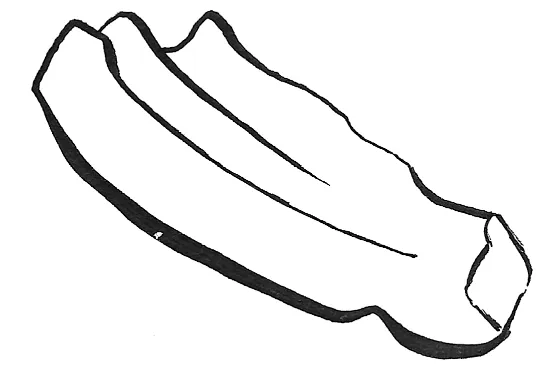

2.0.06 Cloak

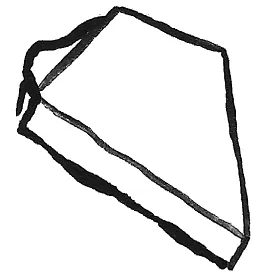

2.0.07 Balance

2.0.08 Dagger

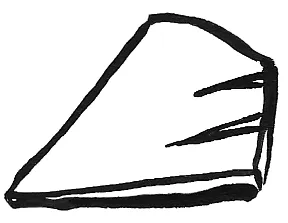

2.0.09 Guard

2.0.10 Lantern

2.0.11 Jutsu

2.0.12 Ruin/Rien

2.0.13 Placing & Withdrawing Pieces

2.0.14 Disarm

2.0.15 Double-Moves

2.0.16 Immaterial Actions

2.0.17 Passing

2.0.18 Devices of Art & Mysticism

2.0.19 Setting Up & Beginning a Game

2.0.20 Impasse & Other Edge Cases

2.0.21 Endings

2.0.22 Untenable Moves

2.0.23 Custom Rules & Extra

REFERENCE

2.0.R1 Alternate Dice for Dagger Throws

2.0.R2 Alternate Board Variant: Mystic Circle

2.0.R3 Time Control

2.0.R4 Additional Terminology

2.0.R5 Notation

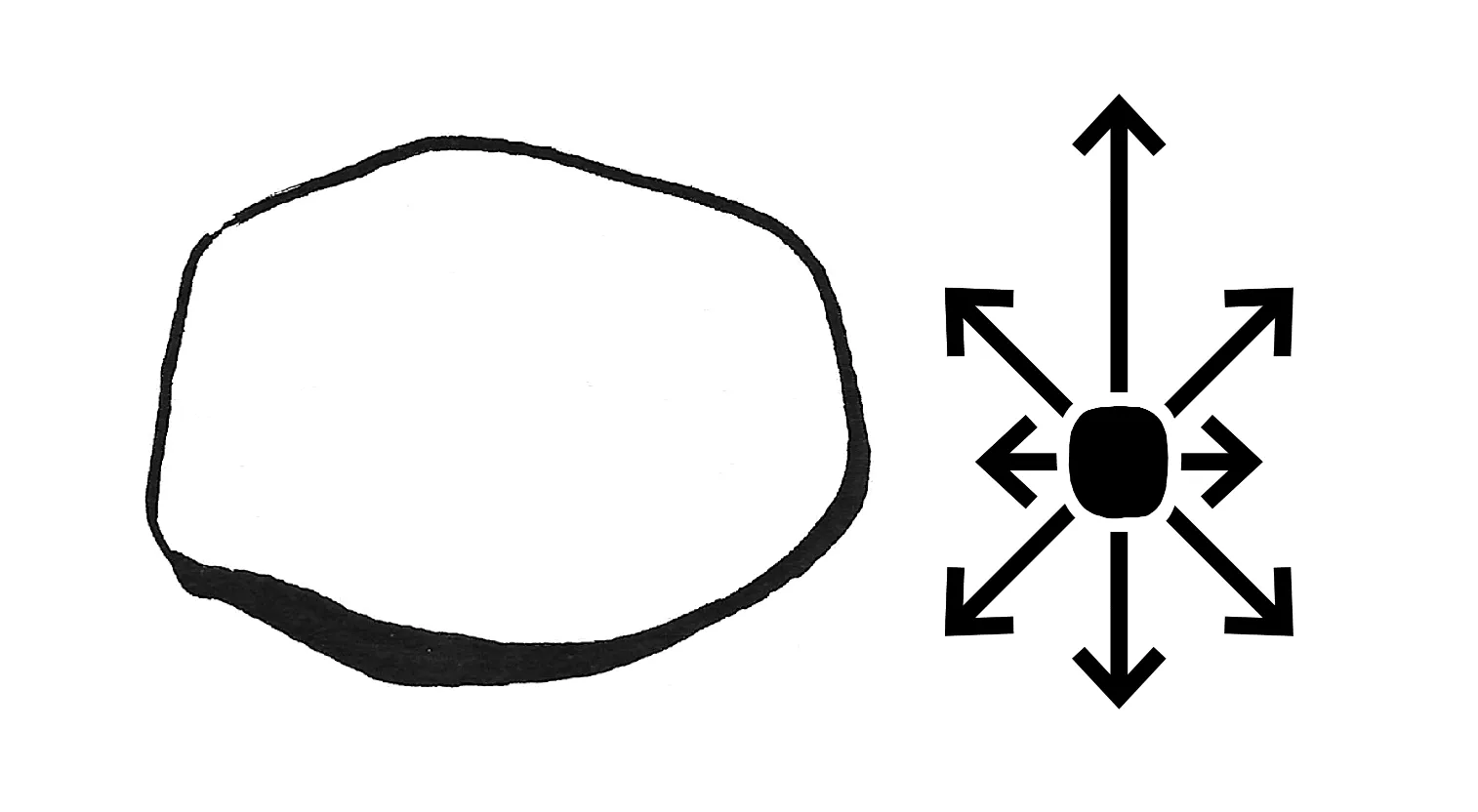

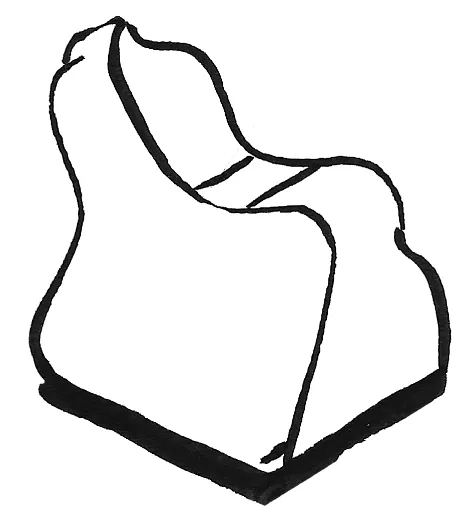

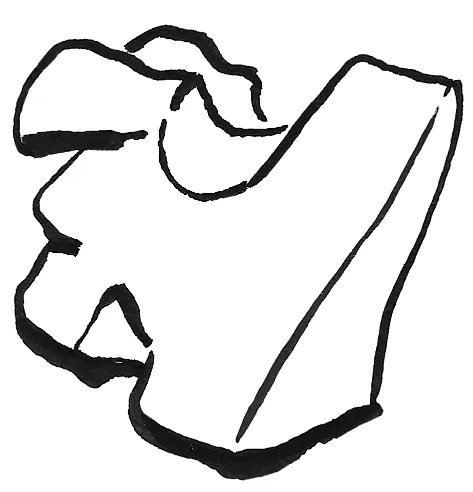

2.0.R6 The Pieces' Shapes in a Standard Set

2.0.R7 Tips for Gathering/Fashioning Pieces

2.0.XYZ STORY

Yes! Isn't that great? Consider checking out the short version first. To get started playing more quickly, review the summary sections in the overview and perhaps just learn the pieces' various special moves as you go.

Summary: The Pieces (In Brief)

The Self

▪ Can take no pieces

▪ Can be checkmated

▪ Movement allows other pieces to advance and/or co-move

▪ Retreat can reset the entire board

The Sword

▪ Range constrained to the Self piece

▪ Co-moves in concert with Self piece

▪ Can take most other pieces

▪ Can be checkmated

▪ Used to perform checkmate

▪ Pushes / interacts with opposing blades

The Engagements

▪ Four of them (whereas only one each of the other pieces)

▪ Can take no pieces

▪ Never permanently lost, only fended

▪ Act as stepping-stones to facilitate double-moves by your other pieces

The Cloak

▪ Extinguishes the Lantern

▪ Can immobilize the Sword temporarily

▪ Provides an escape to the Self

▪ Can be fended, i.e. temporarily removed from the board

The Balance

▪ Transcends the Jutsu

▪ Can trade places with your Sword

▪ Prevents Jutsu from entering its measure when in a measure with the Self

▪ Can be fended

The Dagger

▪ Constrained closer to the Self

▪ Co-moves in concert with Self piece

▪ Player with this piece in play survives if the Sword is lost

▪ Can be used for a special thrown attack

▪ Blade-to-blade moves (like Sword) only on opposing Dagger

The Guard

▪ Bludgeons Balance

▪ Deflects blades

▪ Can co-move in concert with the Self, like Sword/Dagger

The Lantern

▪ Burns the Cloak

▪ Long-range “Glare” attack against Self fends Jutsu

▪ Can be fended

The Jutsu

▪ Subverts the Guard, negates the other Jutsu and itself

▪ Prevents piece drops while in measure with the Self

▪ Used for feinting “intention”

The Free Engagement

▪ Moves like a King to open squares or attacks diagonally as if it were your own pawn

▪ “Meta-moves” on lines of the grid before entering play

The Ruin/Rien

▪ Moves to any open square (but with range constraints)

▪ Inert: Cannot take or fend any piece

▪ Cannot be taken or fended

▪ Antistrategic significance

Introduction & Comparison to Chess

It isn't strictly necessary to know how to play chess in order to play Veney, but chess is indeed the starting point for the basic shape of the game. As an overview, the following list summarizes the game's significant twists on the rules of modern chess (or other regional and historical iterations of the chaturanga game):

- There is no check. Perhaps most significantly, “check” is not called or enforced as in chess. A player in check isn't required to notice it or to move out of check.

- Checkmate must be “followed through.” Checkmate is performed by actually taking the piece in question. This is significant as a way of committing to checkmate, due to the possibility of double-checkmate (see next point).

- Two-way checkmates are possible. If a player is checkmated, it may be possible for them to checkmate in return. If they see this possibility and seize upon it, then both players have lost. This is like a draw, but worse, because you're both dead instead of both alive. (This double-checkmate possibility is truer to a sword fight and provides a small sense of simultaneity, albeit simulated, to approximate the effect of both adversaries being able to make movements at the same time.)

- More checkmate-able pieces, fewer checkmate-ing pieces. Each player has two pieces which are at risk of being taken for a checkmate: the Self and the Sword (or sometimes Dagger), and only one kind of piece which is able to perform a checkmate: a blade, namely the Sword.

- Replaceable pieces. Most pieces attacked are not “captured,” but rather returned to their owner, who often keeps them in reserve and can put them back into play (the inverse of Shogi, wherein pieces are captured and converted). This is to emphasize the nature of competing over immaterial geometry; A deflected attack may simply be reprised without having materially lost anything. As in fencing, the emphasis is on the position.

- Lost pieces. A losing position can, however, lead to the actual loss of pieces. You may expend all the tricks up your sleeve, become suddenly disarmed, or injured. Therefore, pieces are sometimes lost and removed from the game without going back into reserve, just like in chess.

- Reserved pieces. Each player starts with additional pieces in reserve which can be put into play. Pieces can also be withdrawn off the board into reserve.

- Rock, Paper, Scissors. Each piece has the ability to remove only certain other pieces from the game, like rock-paper-scissors, and via different techniques.

- Special abilities. Certain pieces interact with each other uniquely and execute special moves, like trading places or immobilizing the opponent's Sword.

- Passing is allowed. One may choose to “pass” a turn without making a move unless the opponent refuses their pass.

- Double-moves. The players often make two moves or actions in one turn. For example, when the Self moves, the Sword can also move. There are several vectors for double-moves, but they never combine beyond a limit of two moves total.

- No promotion. Neither pawns nor any other piece can promote. Pawns are compensated with other qualities, such as never being permanently lost.

- Stepping-stone pawns. Each player can use their “engagements” (pawns) as stepping stones which grant a second move with the same piece that took the pawn's square. This allows for more complex and surprising movements.

- One piece is shared. The free engagement, a pawn which starts in the center of the board, can be controlled by either player.

- You must take risks. Some pieces are constrained by distance to your checkmate-able Self piece. One purpose of this is that in order to attack your opponent, you must bring forward your critical piece, thus risking its safety in return.

- A board of boards. To achieve the above described range constraints, the board is subdivided into four measures, one successively after the next in a row between the two players. For certain pieces, the constraints of these measures act similar to the “fortress” area of the board in xiangqi and janggi.

- Room to retreat. Each player starts with space retreat into.

- …and the board may reset. It's possible for one player to retreat and reset the entire board without starting a new game. However, attempting to do so may temporarily put that player's pieces at risk until the reset, and you can only do this a limited number of times (or not at all) depending on prior agreement.

- Variable setup. The starting positions of your pieces can be varied to preference or to explore more effective positions, and the process of setting up can optionally be made a part of the game. Custom setup can also be used to determine which player makes the first move.

- A shared axis of attack and defense. Where chess games are played through subterfuge and networked entanglement across a wider field, the shape of this game is much narrower and more direct; it can be thought of in terms of a more condensed game of chess taking place as a gateway between two attacking / defending poles.

- Breaking the rules is a part of the game: A move which breaks the constraints laid out for that piece can be simply called out and reverted or seized upon as vulnerability for attack.

- Chaos & Order are intentional themes. The game is, at present, intentionally over-complicated and open to experimentation, interpretation, and improvement. It will probably change and develop over time—as have the tactics and conventions of both chess as well as weapons systems like the blade.

All of the above are designed to make a chess variant more akin to fencing, but the actual cumulative result of these abstractions is arguably far less apprehensible (and certainly less intuitive) than any kind of physical fight. Ultimately, what it amounts to is open for interpretation.

Three Precepts of Spirit

-

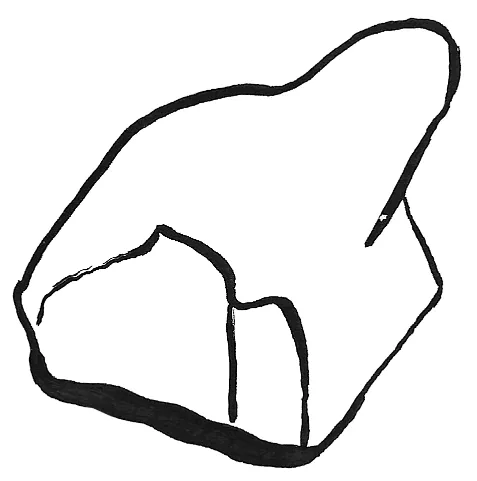

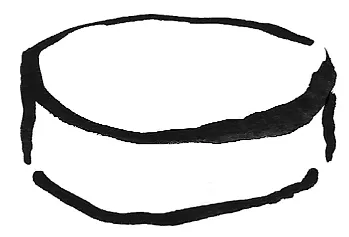

The ideal set is made with found and collected rocks, shells, bones, and other bits of this and that.

-

You can play a casual game with one complete set, or you can play for keeps in a formal game using a token from your own collection as your Self piece; at the end of a game, the checkmated player gives their token to the winner. If you both die, you trade and keep one another's tokens.

- Optionally, some may choose to call their unique Self tokens something special. It is still the basic Self piece for all intents and purposes, but you could also call it your Fighter or your Fencer; you could say that traditionally one player in your set is the Fool and the other is the Devil; or you could call your token by the name of a character it's meant to embody. It may be unclear whether you play as yourself or as a persona.

If you want to quickly get a makeshift set together in order to actually play, you can simply use marked/modified checkers and chess pieces, things found around the house, or even just draw identifying letters or symbols on simple rocks, on coins, on pieces of paper or cardboard, bits of tile or wood, etc. You could also carve or sculpt pieces from all kinds of materials; your options are endless. Take a trip to the hardware store. It's always better to be creative than to be hampered by any kind of dogma. What I'm offering here is simply my own version.

It's also possible to play with half a set, missing many of the non-critical pieces. (See: Custom Rules & Extra)

Playing with Sand

The lengthy complex of rules which follows can be viewed as an experimental sandbox* of game mechanisms and fencing-analogues. Things will change, get dropped, merged or refined over time. This isn’t quite an “open beta,” because there’s no product; there will never be a final version. But it’s something like that.

Since there are just so many special moves and side rules to remember and thus an ever-present possibility of wandering into a technically illegitimate position, I would like to emphasize a more casual culture of play and at most a preference for lenient piece-penalty as the norm for untenable moves during any moderately competitive match, and of course only when called out. This way, it's almost as if breaking the rules is allowed** but with high risk, since knowing the rules—knowing the whole system in detail—is always more effective. To put it in fencing terms, aggressively blundering in bad form can certainly get you somewhere, but a more skilled opponent can capitalize on those mistakes. In game terms, the rules themselves and adherence to them are just another level of gameplay.

*To sort of misuse the term

**Within sociable, obvious limits distinct from deceptive cheating

Overall Play & Goal

The goal of the game is to use your blade to checkmate your opponent either by touch (taking the Self piece) or by disarm (taking their only blade piece) while defending against checkmate in return.

On your turn, you may make one or possibly two of several actions.

- Move: Move one of your pieces already on the board to an open square.

- Take/Fend: Move one of your pieces to a square where it takes or fends another piece.

- ...You can do either of the above with the free engagement, a piece shared by both players.

- Place: Place a piece from your reserve onto the board.

- Withdraw: Put one of your pieces already on the board back into reserve.

- Pass: Pass a turn and do nothing.

- Special Move: Invoke various special moves and aspects of your pieces to perform certain actions not described above.

Additionally, before taking any of these actions, you have the option to first reposition the free engagement if it is not yet in play and then take your regular turn. (More on this later, see: free engagement).

You also can call out an opponent's untenable move for a penalty (or not, depending on how you agree to play), but this isn't a move.

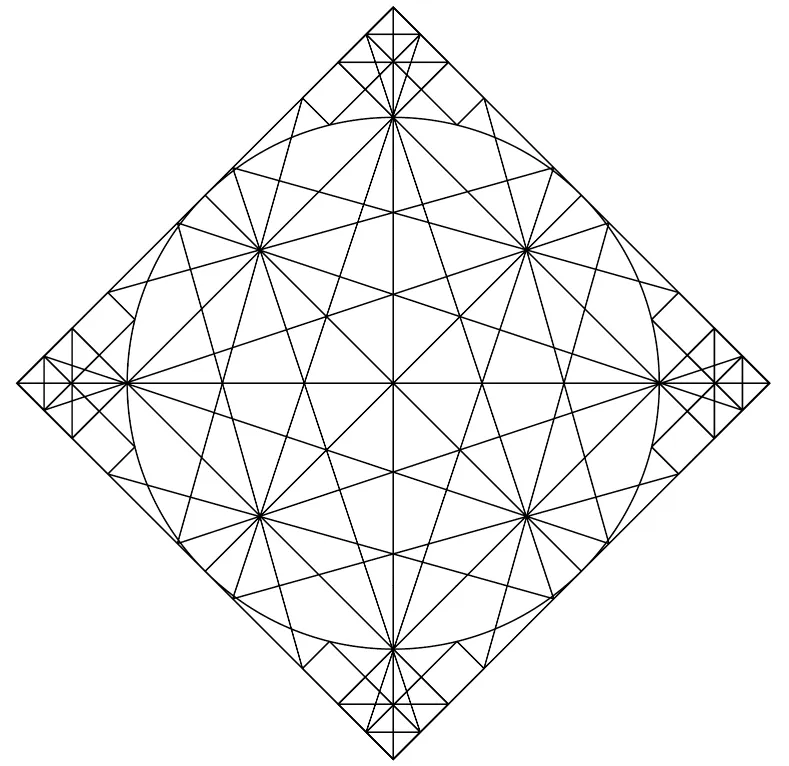

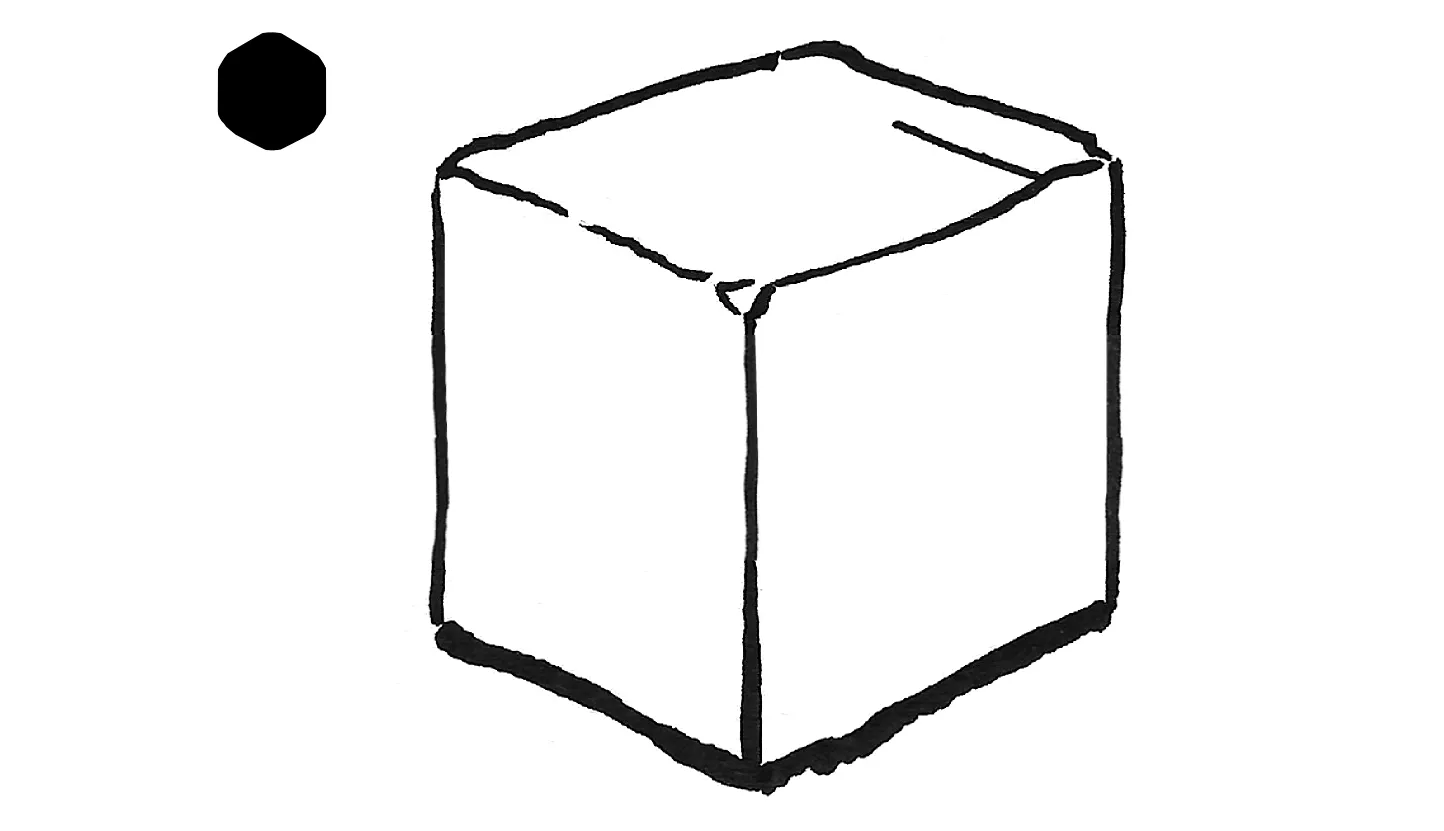

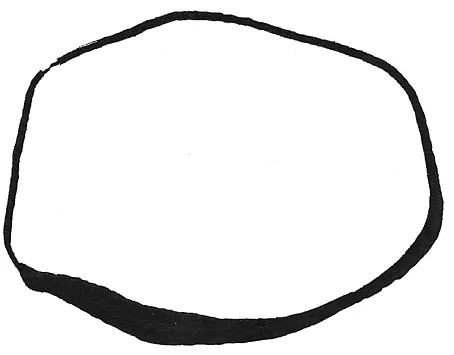

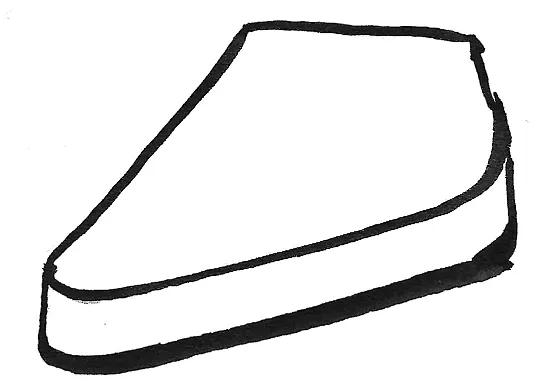

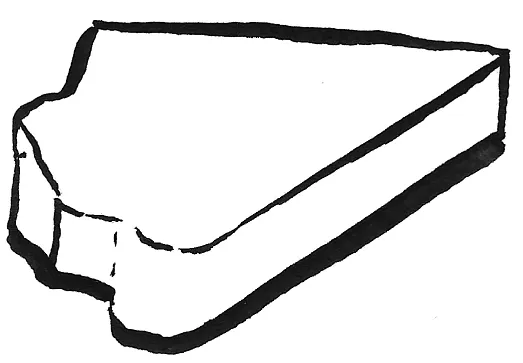

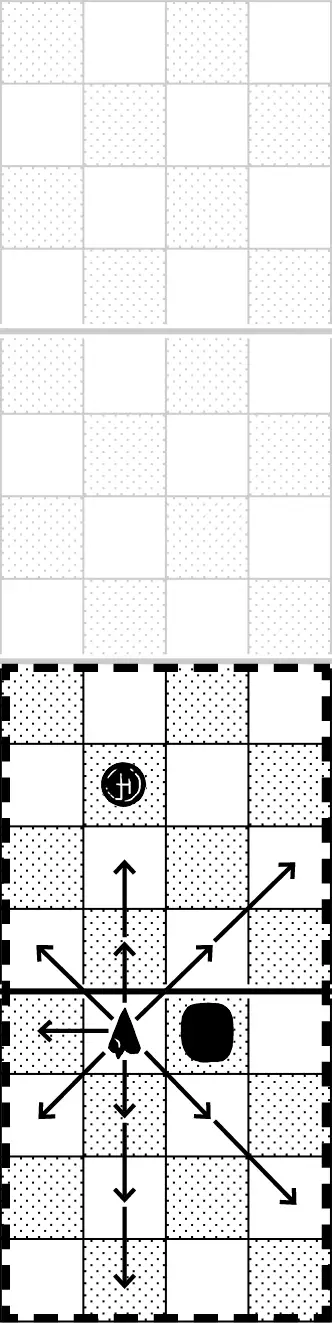

The Board

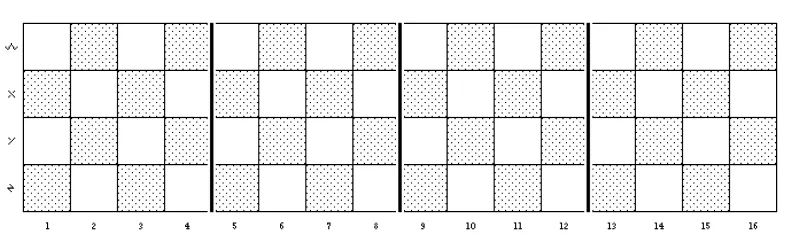

The board consists of 64 spaces arranged in a 4x16 square grid, like a chess board cut in half and put back together in a longer, narrower configuration. The two players sit facing each other on either end of the board, like the fencing piste.

The board is additionally divided lengthwise into four measures, each of which is a 4x4 square grid. The line dividing the middle two measures can also be said to separate the board into two sides, your side and your opponent's. Some more terminology follows: The measures, when viewed from your own perspective, can be called your first measure (nearest to you), your second measure (next nearest), your third measure (the first which crosses onto your opponent's side of the board), and your fourth measure (the furthest from you). Your fourth measure is your opponent's first; their fourth is your first.

The squares are shaded in an alternating pattern, like a chess board. This is not strictly necessary in chess, but here it serves a mechanical purpose for a special piece. Each player should have a light square on the left end of their nearest step (W1 is a light square).

The sixteen lateral rows of spaces, each four-squares-wide, are called steps, representing distance closed between two fencers step by step. The four lengthwise rows of spaces, each sixteen-squares-long, are called lines, representing the lines of offense and defense through which a fencer maneuvers their faculties. (These are named in contrast to chess, where the “ranks” and “files” of the board evoke masses of soldiers arranged for combat in a field of battle.)

Any row of four diagonally adjacent squares can be called simply a diagonal, as they are in chess. Note that each diagonal spans the same distance (four steps) as a measure.

To specify squares, the steps are labeled 1–16, and the lines are labeled W, X, Y, and Z. (Three of the letters of A–D are taken by the names of pieces, so shorthand notation is made clearer by not reusing letters. XYZ and W also nicely evoke three-dimensional space, for fun, but if this makes things more confusing for you, it's okay to call the lines A, B, C, and D.)

To make a set more usable for Blind players, one can affix flat rails along the lines of the grid, like a Senet board. Skewers, chopsticks, or some other straight wooden crafting sticks will work. Small rocks can't fall over like chess pieces do, so they're well suited to this, and the railings have an added benefit of ensuring that results of a Cast Piece will be determined with certainty. Note that the free engagement will need to be able to sit affixed at an intersection atop these rails—using a piece from a set of jacks should work. Texturing the alternate squares creates an alternating pattern.

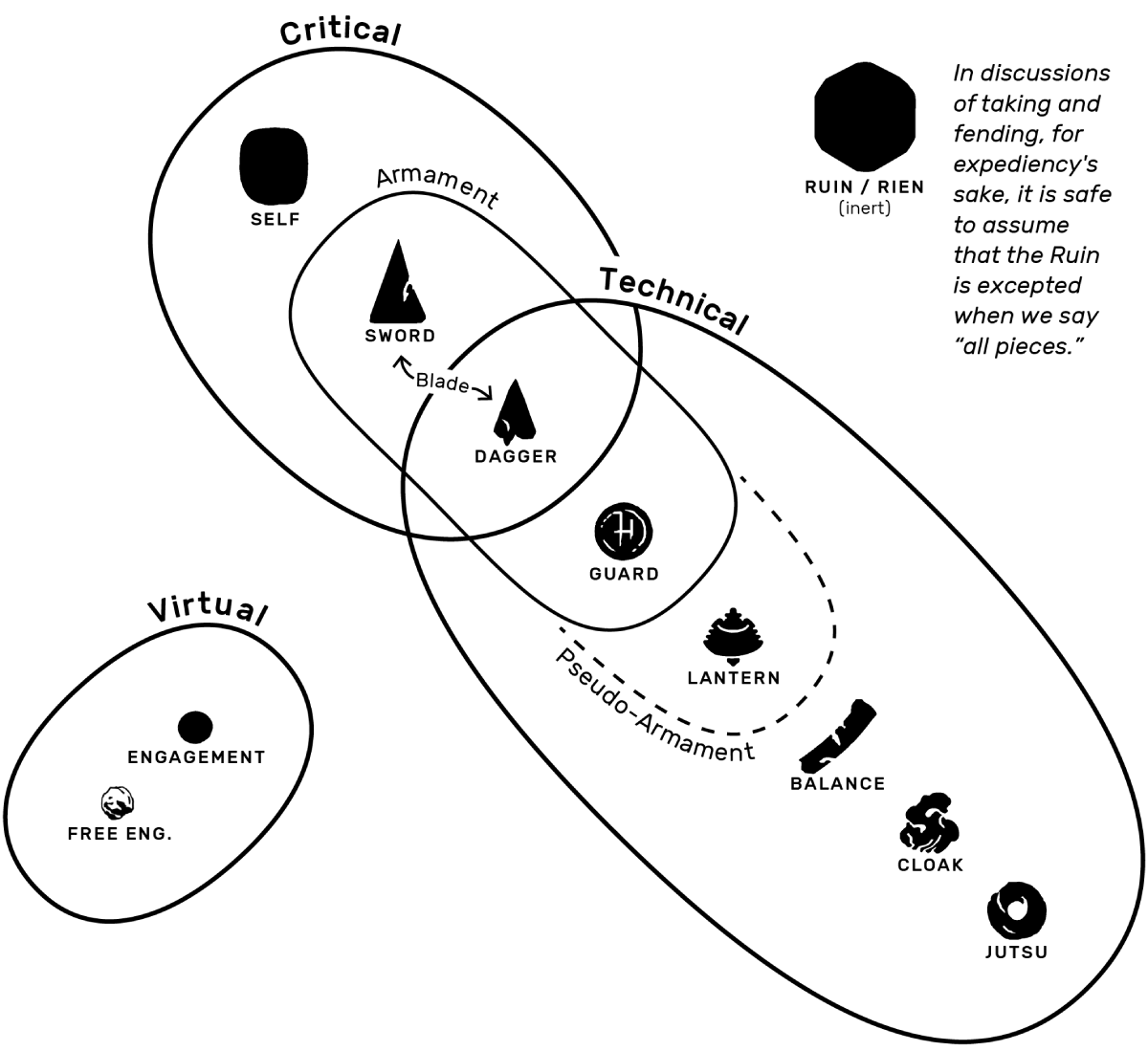

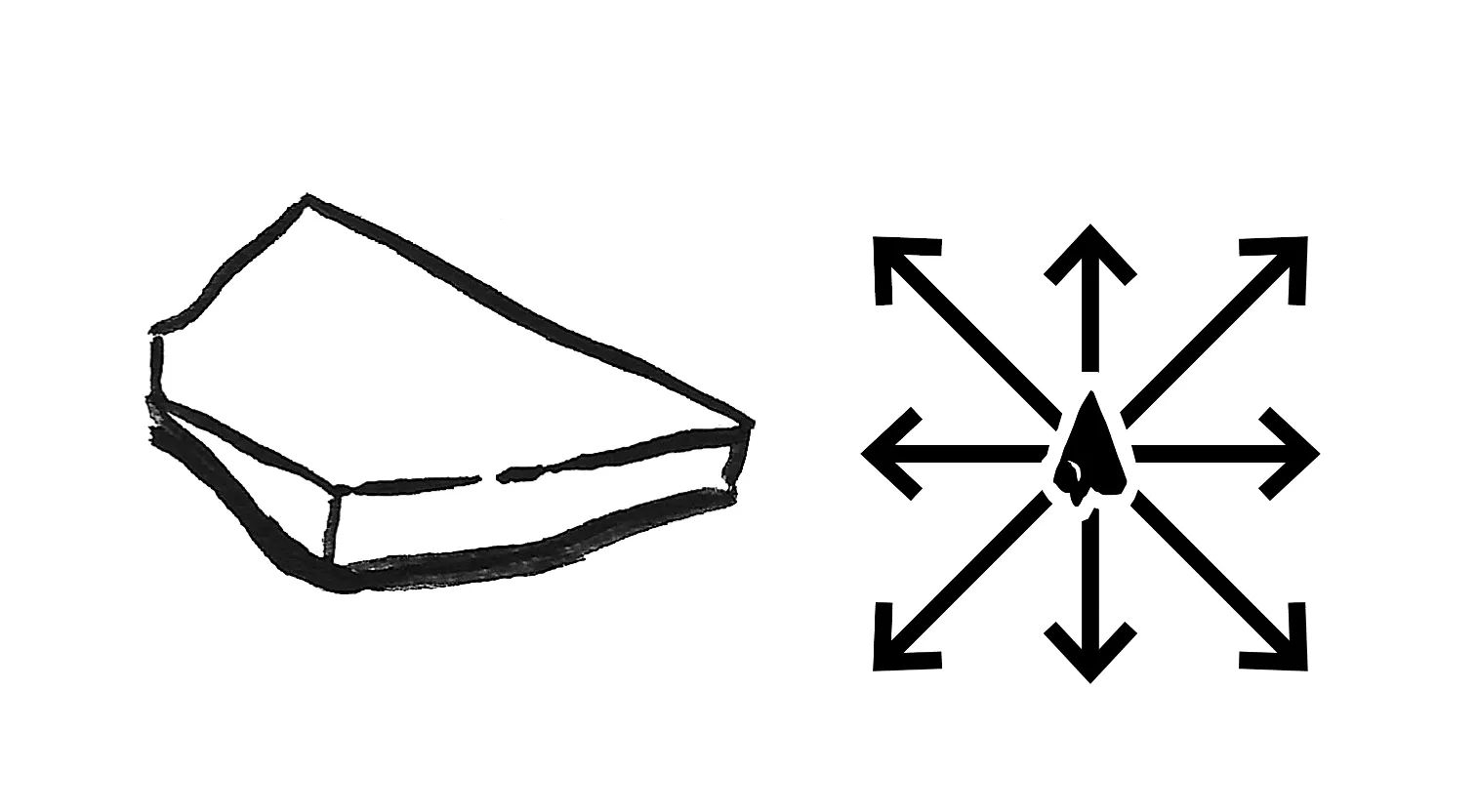

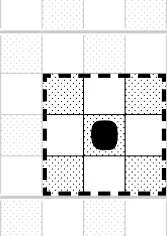

Types of Pieces

Pieces can be instructively thought of as belonging to one of three categories: Critical pieces (Self and Sword or Dagger), Virtual pieces (engagements and the free engagement), and Technical pieces (Cloak, Balance, Lantern, Jutsu, and Guard).

- Critical (Major) pieces: The loss of these is what results in a game over. You need both a self and a sword to fight with. One piece is your life, and the other is how you take life. One (the sword) can take all, and the other (the self) almost none. Both are irreplaceable. (Dagger is considered critical if Sword is lost.)

- Virtual (Minor) pieces: The purpose of the engagements is to outline and facilitate the movement and strength of your sword, to allow for more flexible, complex, and surprising actions by other pieces, and to provide controlled points for your better pieces to defend. They cannot remove any other piece from the game permanently, and they are entirely replaceable. They help to structure the board and the shape of play, like pawns, but can accomplish very little on their own. They also have a virtual function as a sort of wager when expended for a double-move. Thus they can be thought of as markers of the sword's virtual extensions or as an aggregate piece made of multiple pieces.

- Technical (Middle) pieces: These are expendable and often replaceable like engagements, but they are more singularly valuable as they have greater mobility and more complex movements, as well as special moves and aspects that can quickly reshape a moment in the game. Their special uses make them effective on their own, but they are still not capable of taking a critical piece for a checkmate. They can only take or fend other technical pieces and engagements. You can also lose one permanently, to your detriment, but it's not game over. They function on a “technical,” augmentational level to support your critical pieces, to fight for space, and interfere with your opponent's position.

Additional categorizations of pieces useful for explanatory shorthand are the blades, referring of course to the Sword and Dagger, and the armaments, which includes the Sword, Dagger, and Guard—these pieces are vulnerable to disarm. The armaments are all constrained by movement to the Self in some way, but are also allowed double-moves in concert with the Self. The Dagger and Guard are sometimes called the lesser armaments (they're not as powerful as the Sword).

One may also speak of the starting pieces (the engagements, Sword, Self, Cloak, and Balance) and the additional reserve pieces (the Jutsu, Lantern, Guard, Dagger, and Ruin/Rien). The fighting pieces refers to all the pieces other than the Self and Ruin/Rien.

The fendable pieces are all except for the Self, Sword, Dagger, Guard, and the Ruin/Rien (see next section on fending).

Note: The Ruin/Rien, an optional piece, does not fit into this framework. It's most like a technical piece, but its inert role among other pieces disqualifies it from most everything of what the rules have to say about technical pieces.

Note: The Ruin/Rien, an optional piece, does not fit into this framework. It's most like a technical piece, but its inert role among other pieces disqualifies it from most everything of what the rules have to say about technical pieces.

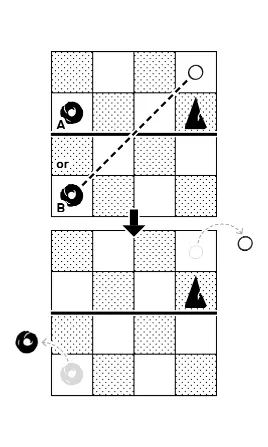

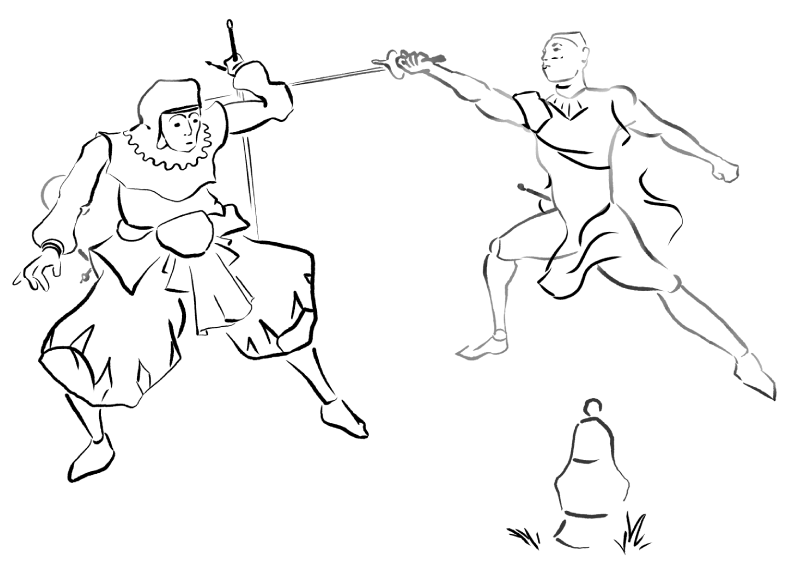

This diagram is not important to understand. Nor was this entire section. But you might wish to.

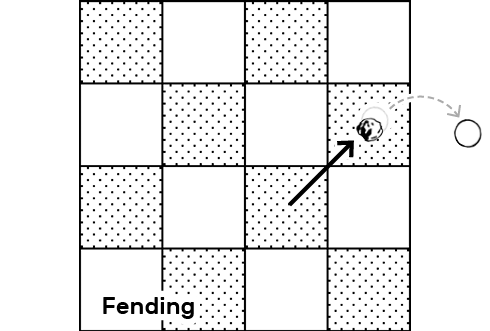

Terminology: Take or Fend?

There are two different kinds of “taking” a piece in this game: take and fend. When an opponent's piece is taken, the attacking player literally takes the piece and removes it from the game permanently—just like in chess. Most often, however, a piece is instead fended, i.e. returned to its owner's reserve. Your pieces can also be withdrawn. These distinctions make it necessary to clarify our terminology in order to talk about the game.

Fended: When one piece attacks another in such a way that the latter is returned to its owner instead of being removed from the game entirely, we say that the attacking piece fends the other. The piece has been fended or fent, i.e. abstractly turned away, fended off, derailed, subverted, supplanted, surpassed, etc. but not eliminated. (You can imagine, in the mechanics of fencing, a movement which transfers one interaction into another in a long series of strategically transmuting engagements). You can either hand the piece back to your opponent or put it in their reserve yourself.

Taken: When one piece takes another and permanently removes it from the game, we say that the attacking piece takes the other. The piece is taken or lost, depending on perspective. (For flavor, you could say that a piece is “lost,” or “destroyed.” The choice of word is irrelevant to the gameplay. For example, an actual cloak that ensnares a sword and is then cut loose can be understood to be destroyed. An actual dagger disarmed by a sword would not be destroyed, but rather lost. More to the point, the main analogy here is that one fencer has lost something; lost tempo, distance, control, composure, balance, blood, limb function, armament, etc.)

Discarded: The player who removes a taken piece from the game “discards” the piece.

Withdrawn: When a player spends a turn putting one of their own pieces back into reserve, that piece is “withdrawn” from the board.

Removed: This is an unspecific word that could be used to describe any of the above. (“The piece is removed and discarded.” / “The piece is removed from the board and put into reserve,” / “The piece is removed from the game,” and so on.)

Captured: This word is not used here, or at least not in the same way as in chess, because the battlefield analogy of raiding and captive-taking does not apply. The way that Shogi involves converting captured pieces is instructively not applicable. The one place this word does appear is to describe the Cloak's special move of “blade capture,” an entirely different thing, when a fencer grabs their opponent's blade or otherwise restrains it from movement.

Pieces that are taken/lost should be put into a shared discard pile, not put into your own reserve. (This is actually important due to certain game elements like the self-negation of Jutsu-takes-Jutsu.) The pieces can be discarded:

Pieces that are taken/lost should be put into a shared discard pile, not put into your own reserve. (This is actually important due to certain game elements like the self-negation of Jutsu-takes-Jutsu.) The pieces can be discarded:

- Back into their bag/storage container

- In a dish or tray beside the board

- In a pile used by both players, away from the immediate edge of the board

- Atop a handkerchief, paper or book used to designate a discard area

Note: The natural impulse to speak of “taking your own engagements” is technically incorrect, because these stepping-stone engagements are not “taken” in the sense defined for the game's rules. Nevertheless, you would be understood.

To “see” a piece is a chess concept with applicability here. A piece that “sees” another has a movement pattern which could land on the square occupied by the seen piece, whether or not it can actually take or if it would be wise to do so.

Attack: This is a flexible term which may describe the actual move to take/fend/capture or just the possibility of it, i.e. “seeing” with actionable threat.

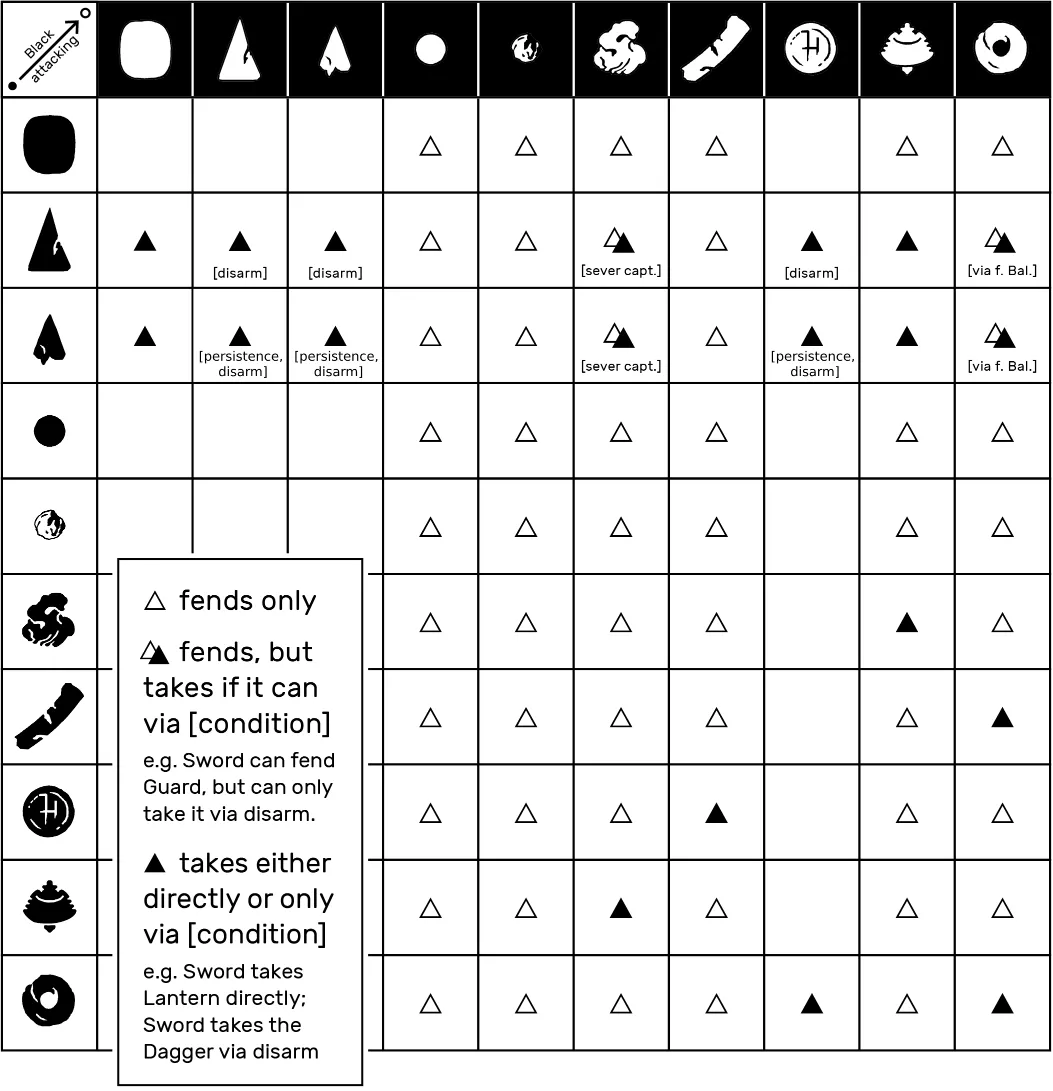

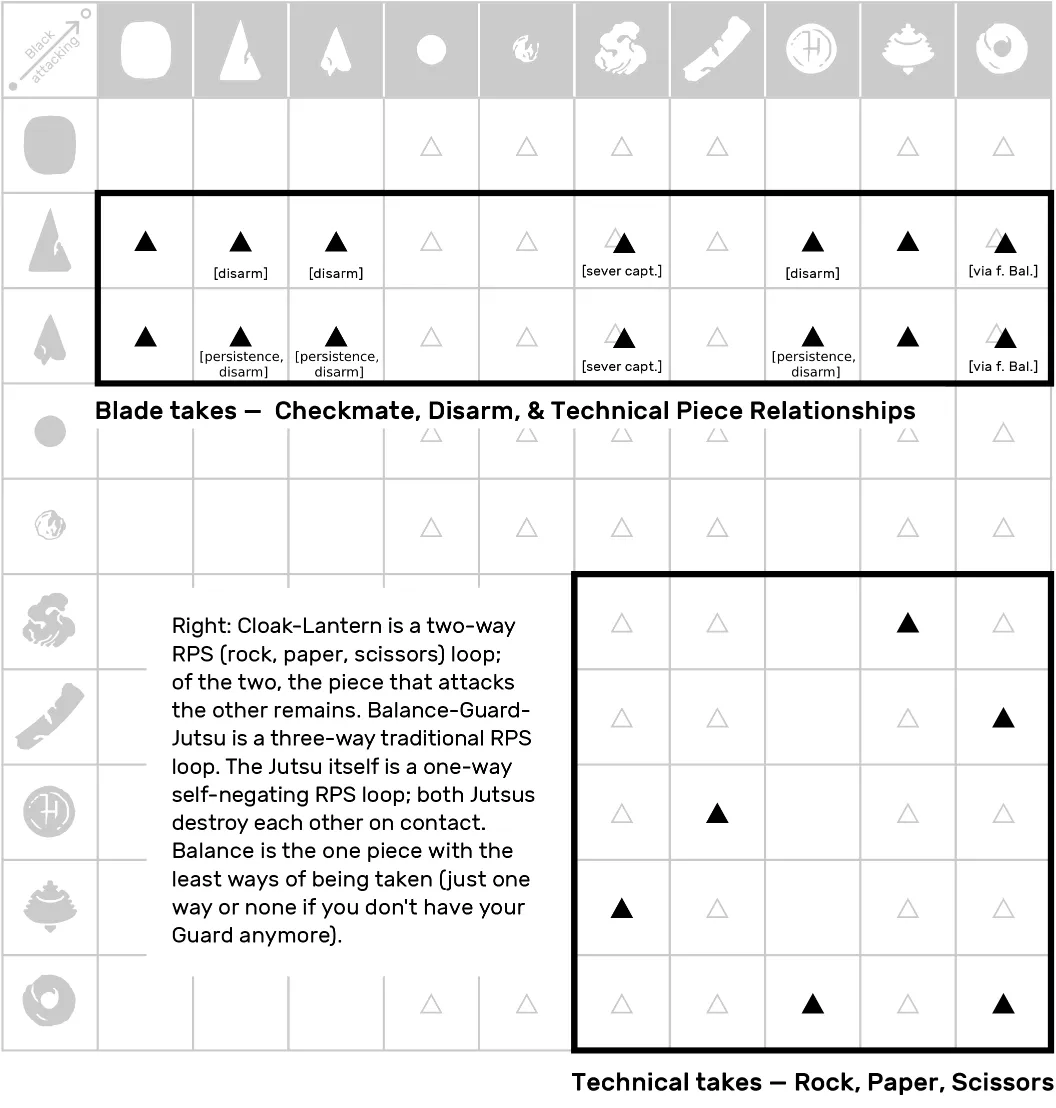

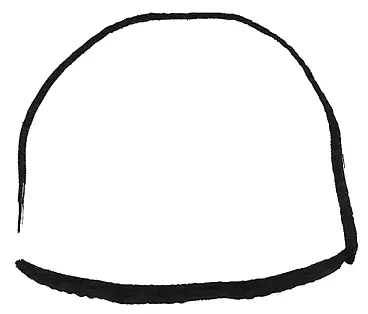

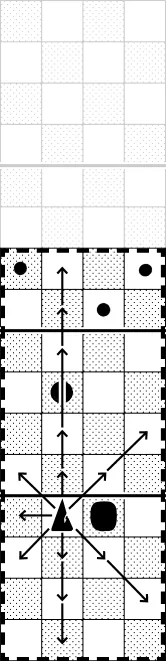

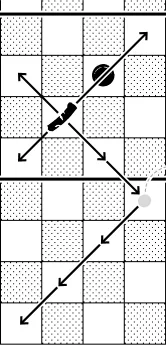

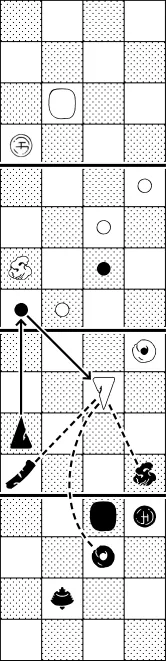

Summary: Taking & Fending

(Black attacking in below chart)

It's not necessary to immediately review these rules in detail, but here's a chart for future reference. In general, the take / fend relationships are as follows:

- Critical pieces and armaments are never fended, only taken. All other pieces are fendable.

- All pieces fend all non-armament, non-critical pieces (unless they can take).

- Armaments (Sword, Dagger, Guard) are only taken by disarm, except for Jutsu's subversion of Guard.

- Blades take middle/technical pieces according to certain piece-to-piece relationships.

- Middle pieces take each other via rock-paper-scissors loops.

- Engagements (including free engagement) are never taken, only fended, and can take no pieces.

All your pieces (except Ruin) can also step-stone your own engagements.

The Ruin/Rien is inert and not included here.

Cloak-Lantern is a two-way RPS (rock, paper, scissors) loop; of the two, the piece that attacks the other remains. Balance-Guard-Jutsu is a three-way traditional RPS loop. The Jutsu itself is a one-way self-negating RPS loop; both Jutsus destroy each other on contact. Balance is the one piece with the least ways of being taken (just one way or none if you don't have your Guard anymore).

The Pieces, Their Movements & Specials

A Note on Abstraction

Most of these pieces are named after real things which can be used in fencing, but the game does not necessarily insist that they literally represent those things. It is, and it isn't. The Cloak, for example, is thought of as a cloak because that's evocative and interesting, and it needed a name, but it's also just another one of several pieces, one of several dimensions, so to speak, which outline an abstract representation of positional interaction between two blades and two bodies.

Specials: “Aspects” vs. Moves

The pieces' special moves can be divided into the categories of moves and aspects. A special move is available conditionally based on interaction and/or movement between two pieces, initiated by the one performing the special move. An aspect is either constantly in effect or available to invoke at any time, not necessarily by moving a piece, and sometimes initiated by a different piece to whom the aspect doesn't belong.

For the purposes of these rules, the term “adjacent” refers to the position of two pieces which are in squares that touch either orthogonally (sharing a side) or diagonally (sharing a corner).

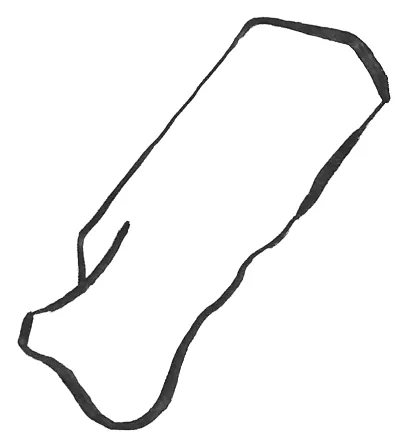

Self

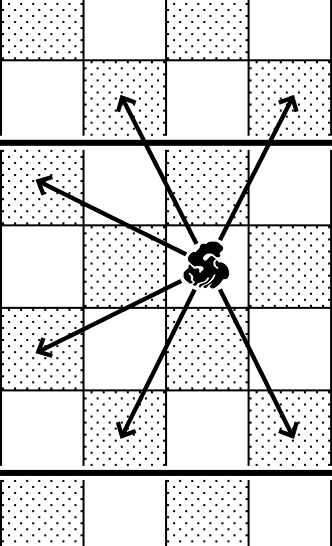

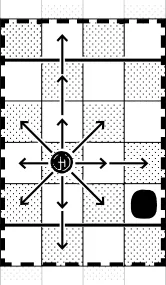

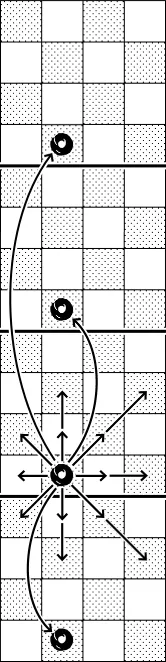

The Self piece is analogous to the king in chess. Its basic move is the same: one square in any direction, orthogonally or diagonally. Additionally, it can lunge forward and return backward (straight or diagonally) more than one space, depending on which measure it moves from. The Self cannot leap over pieces.

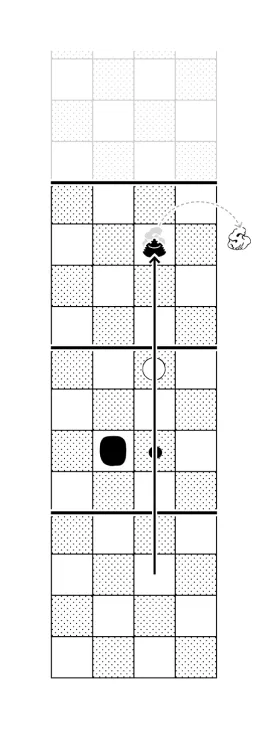

The sequence to remember is 4, 3, 2, 1. From the first measure, the Self can lunge forward (or diagonally forward) up to 4 spaces and only step back 1 space. These distances are increased or decreased as you go up and down the measures. From the second measure, the Self can lunge forward up to 3 and return as many as 2 spaces. In the third measure, it can lunge forward 2 and return as many as 3 spaces, and in the fourth measure it can only step forward 1 but can return a full 4 spaces.

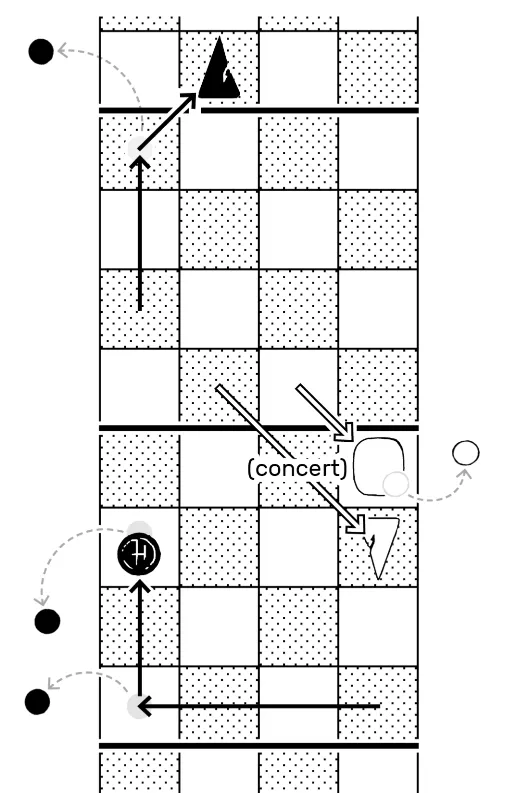

Below: Some examples of the Self's available movements.

Taking: The Self can only fend your opponent's fendable pieces as well as the free engagement, and can move by stepping-stones through your own engagements.

Vulnerability: Can only be taken by the Sword or Dagger (checkmate).

Aspect: Concert

When the Self moves, the Sword or an armament may also move simultaneously, in concert with the Self. The two pieces move without blocking one another (as with a “castling” move in chess).

The armament's range constraint is based on the position of the Self at the end of this double-move.

Concert is performed by picking up both pieces in one hand, Self first (similar to the rules of castling in competitive chess), then placing them, either one first. Handling the pieces as such may take a bit of practice and dexterity. For accessibility reasons, this whole formality can be skipped by simply declaring the move out loud just prior, e.g. “I move the Self and Dagger in concert.” Or nevermind any of this fuss.

Note: Self and armament moves in concert can be combined with stepping stones, but the engagements don't grant an extra move (because you must pick one method of making a maximum two moves). For more on this, see Double-Moves.

Special move: Retreat

If the Self steps back four steps in the first measure to leave the board entirely (requiring four turns), this player has played a retreat. The board is reset and play continues without starting a new game. However, lost pieces stay discarded and are not replaced on the board or in reserve upon retreat.

Retreats can be limited to a certain number, to no retreats, unlimited retreats, or with different allowances between players of different skill. (One retreat each is the basic choice, which approximates the length of a piste, roughly two boards, and thus the distance allotted to each fencer if each square represents about a foot of distance.)

The players reset to the default baselines as if setting up a new game (on steps 3 and 5 for one player, 12 and 14 for the other) using the pieces they already have on the board and all four of their engagements. If you had additional pieces in play and more than will fit on your starting step behind the engagements, you may either place them on the next step behind or put them into reserve. The free engagement is reset to the center.

If the game was started using custom setup methods, the reset can be done using the same process but again with only the pieces that were already on the board prior to the reset.

Retreat is impossible if your opponent's Self piece is on your side of the board. Note, however, that this could be used to your advantage to bait the other player forward with a step back, when your aim is not to continue withdrawing into a reset but rather to attack.

The final step of a retreat necessarily precludes movements in concert or any other double-move; after one player initiates a reset of the board, it is the other player's turn.

A game reset upon retreat has not ended, and neither player has yet won or lost (unless the retreat limit has been accidentally surpassed, which is considered a resignation).

It is not possible to retreat off your opponent's end of the board, which has to do with the abstracted notions of directionality which define the space of the game. For more on this, see the notes on “Directionality” in the Impasse & Other Edge Cases section.

Below: The Self retreats off the board

Sword

The Sword piece is analogous to the queen in chess. It is your most powerful piece, used to checkmate, and you only have one. If you lose your Queen in chess, and your opponent still has theirs, it is commonly understood that you are doomed. This isn't necessarily always true in chess, but with regards to a sword it is a near certainty.

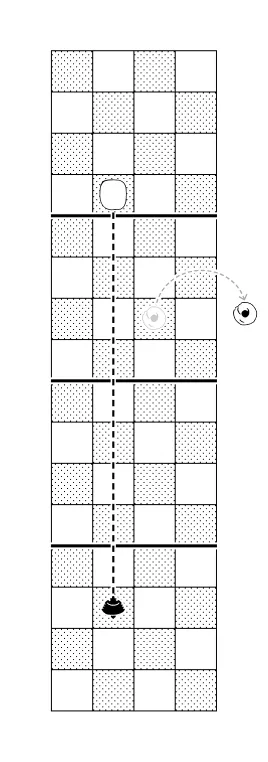

The Sword moves like a queen—any number of spaces in any direction, orthogonally or diagonally—but only within certain range constraints. It can only move in a measure either the same as that which is occupied by the Self or one measure outside of it (in either direction), plus any step further if you have at least one engagement in that step. (Thus, a Sword can certainly never reach an opponent so long as both players' Self pieces haven't advanced out of their first measure.)

The Sword can leap over any of your own pieces except the Self (since you can't, or shouldn't, pass a sword through your own body).*

*The Self's special “concert” can allow a movement, similar to castling in chess, which circumvents the rule against a Sword or Dagger leaping over the Self. This doesn't always work—you may have limited safe or available squares, and the Self cannot end a concert move in the same square where it started.

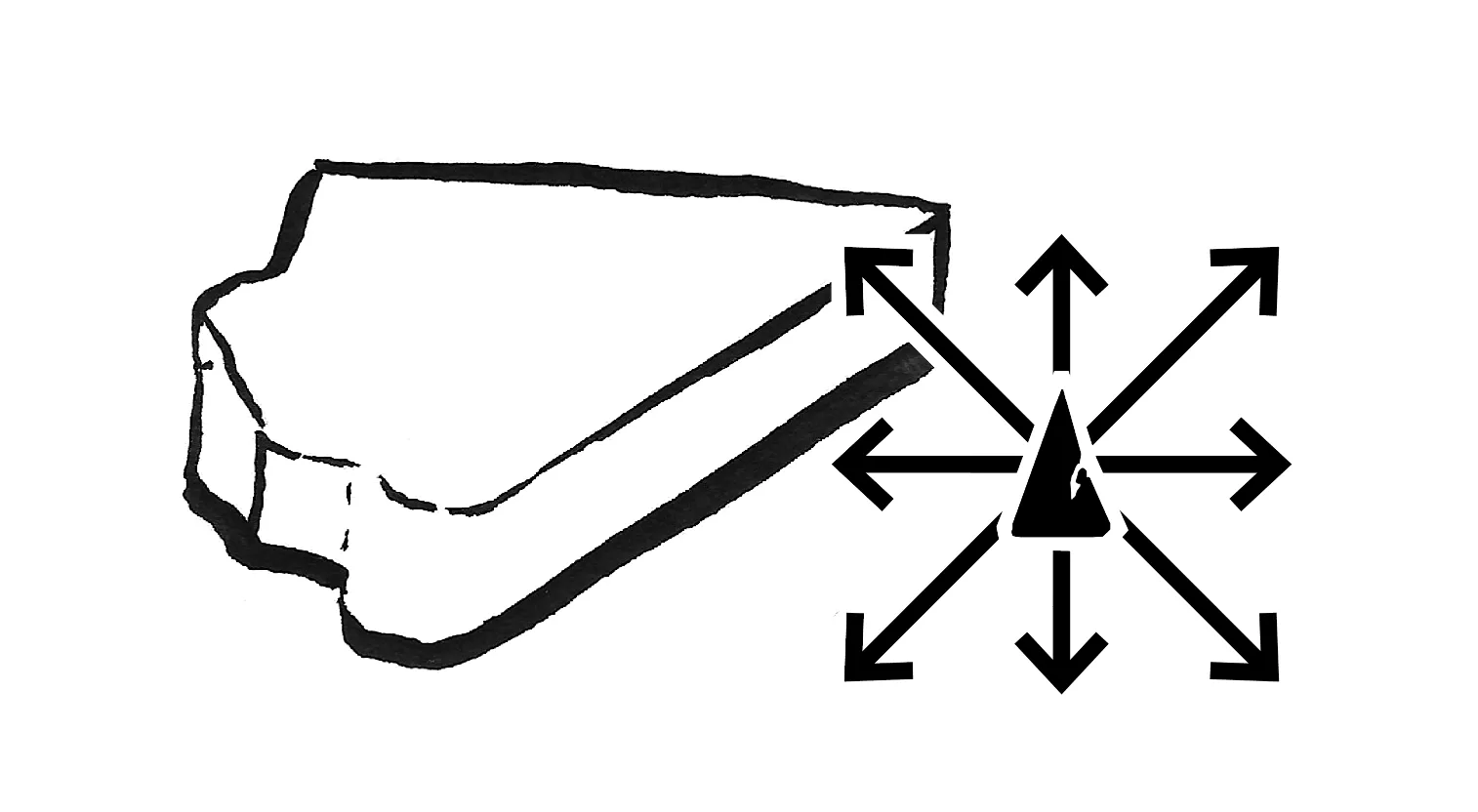

Below: An example of the Sword's range [within the dotted lines] and available movements [actual movement capabilities indicated by the arrows].

Your Sword is the primary piece used to take the opposing Self for checkmate, although the Dagger technically can as well.

Taking: The Sword fends all opposing fendable pieces unless it can take as follows…

- Balance is never taken, only fended (shadow-stabbing).

- Lantern is always taken, directly (shattered).

- Cloak is only taken in counter-action, by cutting free from its special move (severed).

- Jutsu is taken indirectly, by fending Balance (shadow-stabbing).

- Engagements are only fended.

- Armaments — Sword, Guard, and Dagger — are taken only via conditions of disarmament.

- Self is taken directly, as checkmate.

- Ruin/Rien cannot be taken or fended.

Vulnerability: The Sword cannot be fended, and can only be taken by the opposing player's Sword (or Dagger, if their Sword is lost) via disarm conditions.

Special move: Cavazione (Offensive)

You may trade your Sword's place with an opponent's blade by cavazione when the two pieces are adjacent (orthogonally or diagonally) both on your opponent's side of the board.

This can be the second in a double-move by stepping-stone (see engagement) or a move in concert with the Self.

Special move: Opposition (Defensive)

Your Sword may push an opponent's blade by opposition when the two pieces are in-line with one another, unobstructed, and both on your side of the board. This move can travel any distance into consecutive open squares, in a straight line, without moving your Sword beyond the center line.

This too can be the second in a stepping-stone double-move or a move in concert with the Self.

The opponent's blade may be pushed beyond its normal constraints, potentially an effective method of trapping a blade for disarm.

Below: Examples where the black Sword initiates Cavazione and Opposition

Where is the parry?

In a game based on fencing, one might imagine the action of a parry to be a critically important inclusion. Rather, in chess and all chaturanga-like games, your effective preplanning and the nature of the gameplay in general consists of deflecting, derailing, and interrupting your opponent's attacks or threats (i.e. projected attacks)—This already is an abstract parrying-like mechanic inherent to chess.

Furthermore, it makes sense that something as central to fencing as parrying would have to be more abstracted and mechanically dispersed than simply making a move which says “I parry the attack.” There might as well be a move which says “I fence.” (To press the point, it can prove somehow both game-breaking and a bit useless to allow players to merely intercept what would otherwise be a checkmate. There are cumbersome ways to make it work, but it misses the point. This is all made unnecessary by simply embracing a more fluid, abstract interpretation of the parry.)

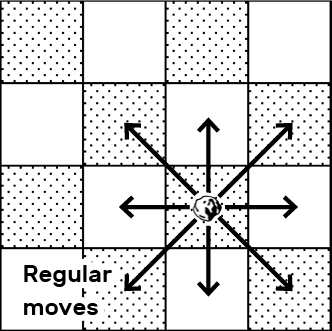

Engagement ...or “pawn”

The Engagements (called “pawns” for short) move like pawns in chess, one step forward into an open square, or one step diagonally forward to take an opposing piece.

Similar to chess, they can advance more than one step within your second measure. Since the board is longer, we allow them to move forward 1–3 spaces until they reach the center line, as long as they aren't blocked (not only on their first move, as in chess). Engagements cannot leap over pieces.

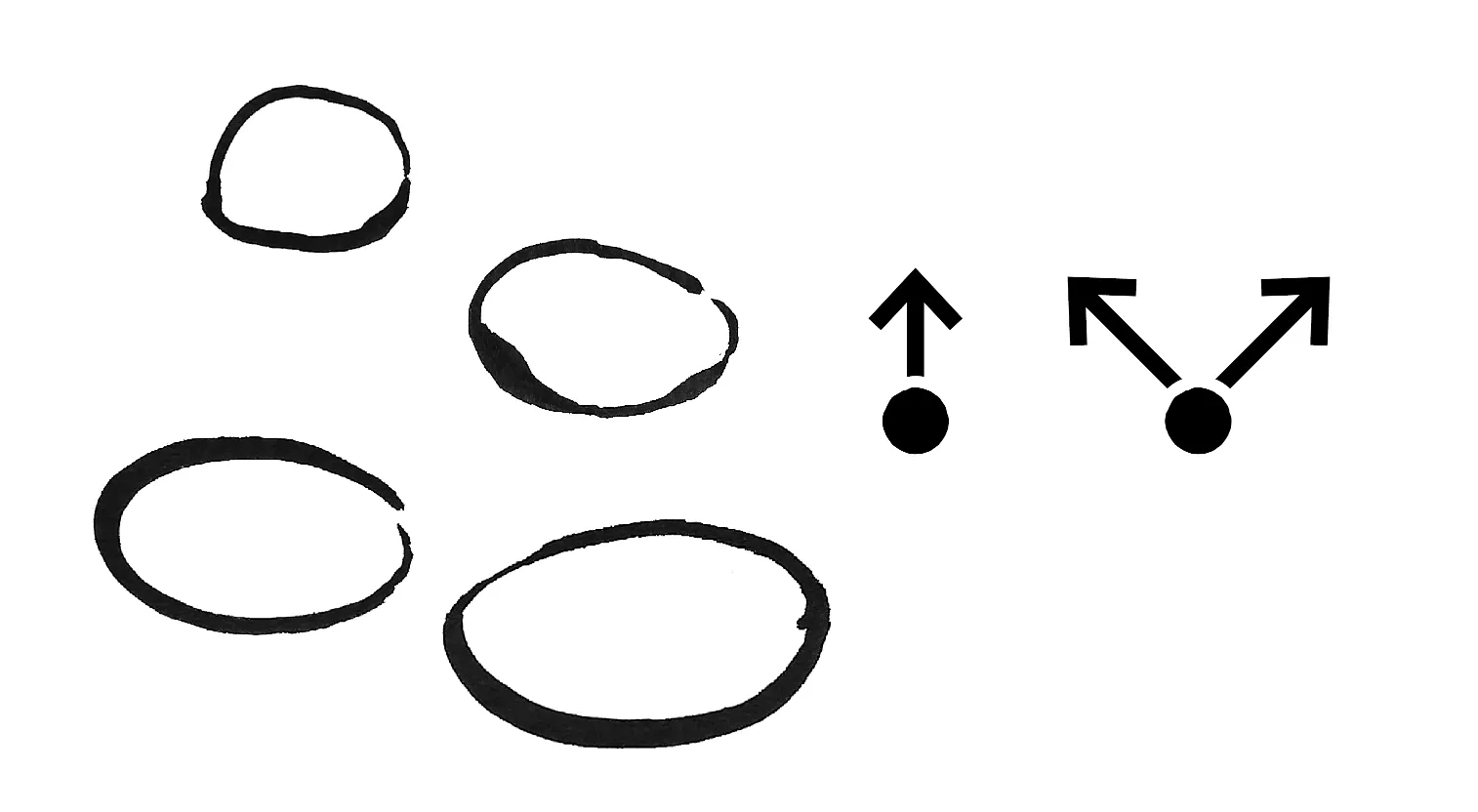

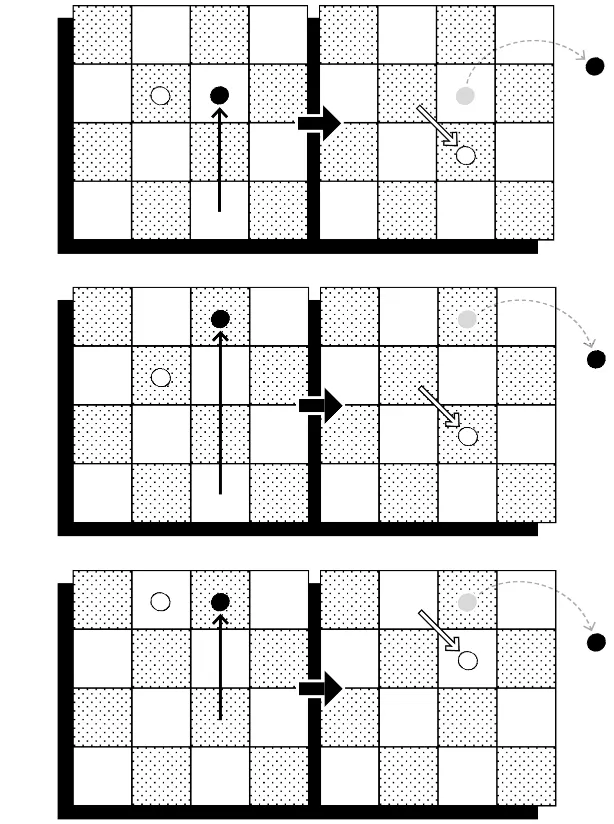

Below: Pawn movements

Taking: Engagements fend other fendable pieces, but take nothing.

Vulnerability: Engagements are fended by all pieces. Engagements are never taken.

Aspect: Stepping Stones

Any of your own pieces may move onto the square occupied by one of your own engagements, which is then removed from the board to reserve. This is called a step-stone move, or simply stepping stones.

The piece that moves by stepping stone is also granted the option to make a second move from that square on the same turn. This is called a double-move by stepping stone, or a double-move by engagement.

A double-move never leads to a third; you can take two engagements but the second doesn't grant another move. You are also making a wager with stepping stones; is it worth the temporary loss of a pawn? If you ever want to replace it, you will need to use a whole move to do so.

Note that you can use an engagement to step-stone on another of your own engagements, which does grant it an additional move. It may open a line. There isn't really much of a reason to do it.

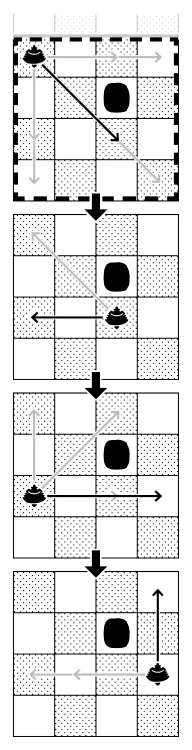

Below: Three examples of double-moves with a stepping stone. In the white example, the Sword actually moves by concert.

Special move: En passant

Just as in chess, your pawns are vulnerable to en passant when they move more than one space and pass an opposing pawn that threatens the first of these squares. The opponent's pawn may fend as if yours had made only a one-square move.

Below: Three examples of en passant

Why do pawns do that?

You may be interested to know that the purpose of the extra-step pawn moves, just as in chess, is simply to get the game started faster and to rapidly build opposing structures of engagement.

Chess defines this rule differently, but here, these pawns can move first one square and then later move two squares; or even, rarely, one square (into the second measure), and later three squares.

En passant is intended to ensure that the extra-step allowance does not backfire and circument the same process it was meant to accelerate.

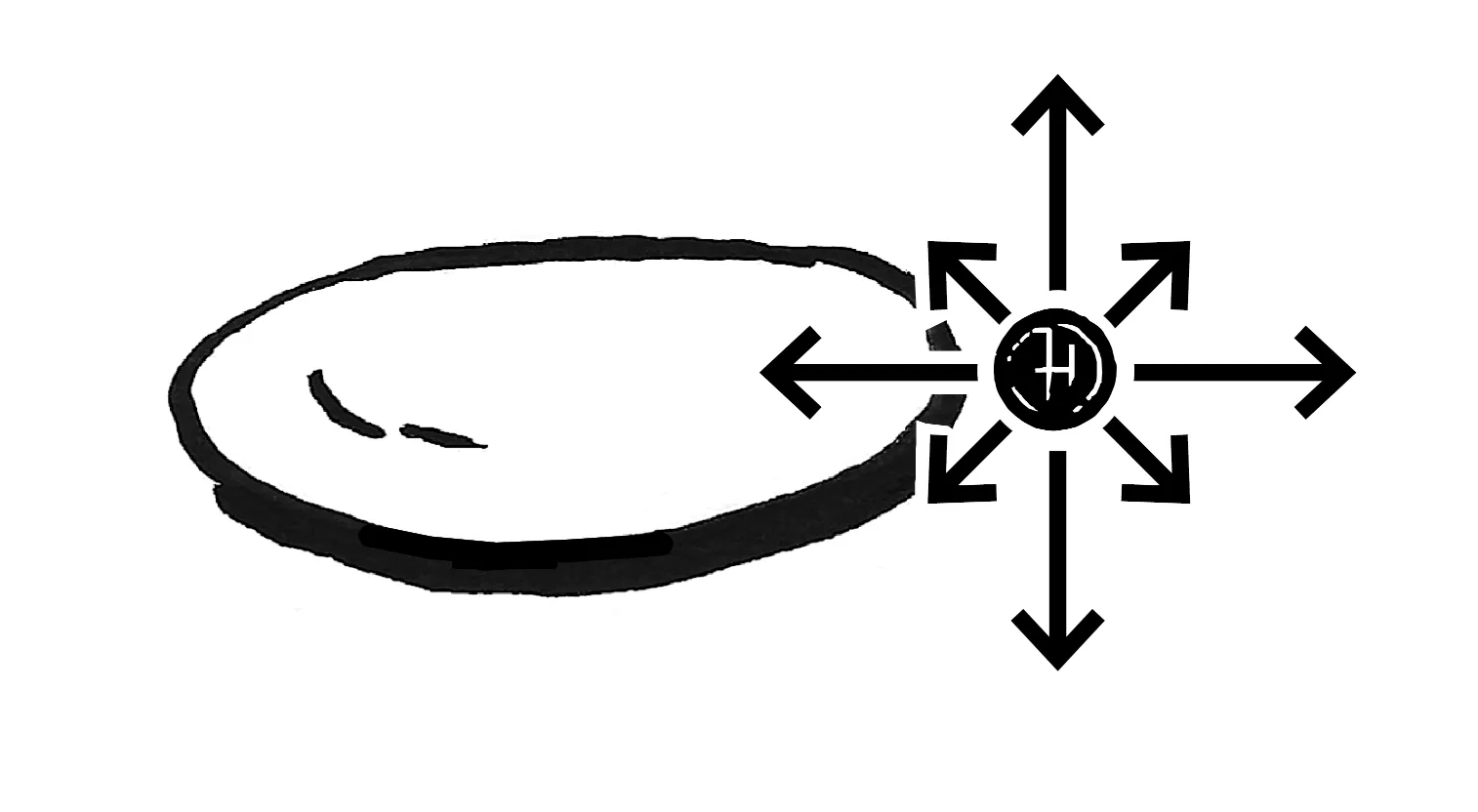

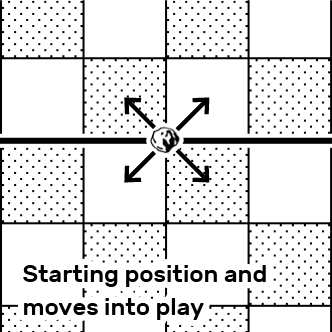

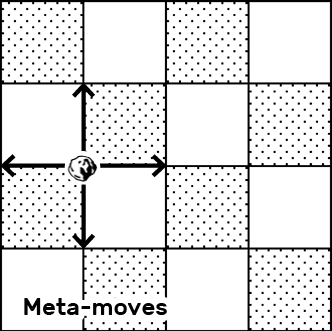

The Free Engagement

...credit to The Verdigris Pawn, by Alysa Wishingrad

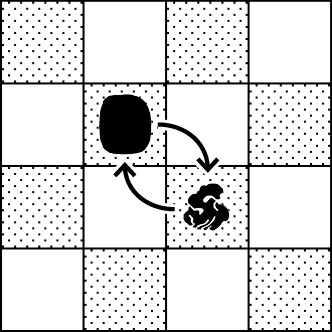

This shared piece begins the game in the exact center of the board, on the intersection of the central grid lines, out of play. To put it into play, one player may move it into any open space of the four squares it touches (this move cannot be used to take a piece). From there, a player may move the free engagement as follows:

When in play, the free engagement can only be moved by the player whose pieces correspond to the color of the square (black or white) occupied by the piece at any given moment. This player is said to have possession of the piece. Possession also allows a player to leap over the free engagement with a blade, to use it for a double-move by stepping stone, or to perform en passant.

When moving without taking, this piece moves like a king—one square at a time in any direction orthogonally or diagonally on empty squares. When taking pieces, it moves only diagonally forward, as if one of your own engagements.

Below: Four different kinds of movements by the free engagement

Taking: Like a normal engagement, the free engagement fends other engagements and fendable pieces, but takes nothing.

Vulnerabiliity: The free engagement can be fended by any piece. When fended, the free engagement returns to its starting point.

While the free engagement sits out of play, either player can reposition it one point along the intersections of the grid before making a normal move for their turn.

These meta-moves let the players attempt to advantageously pre-position the piece before it actually enters play.

- A meta-move must be made before any normal move of your turn; however...

- You may meta-move and then pass. (For the purposes of the rules of passing, this counts as a pass.)

- You cannot meta-move and then declare intention on the same turn.

The free engagement never moves more than one square like a normal engagement may.

If the free engagement is pushed back and forth on the same two squares, repeating a position three times (i.e. if it is pushed back to where it just came from twice in a row), the player whose turn it is may choose to end this cycle by returning it to its starting point and then make any other allowed move.

This piece represents a point of physical contact between two engaged blades which is disputed and subverted by the pressures of opposing forces.

Cloak

The Cloak is analogous to the knight in chess, moving one square orthogonally plus one square diagonally (or vice versa) away from where it started the move, in an ‘L’ pattern. The cloak leaps over any pieces in its path.

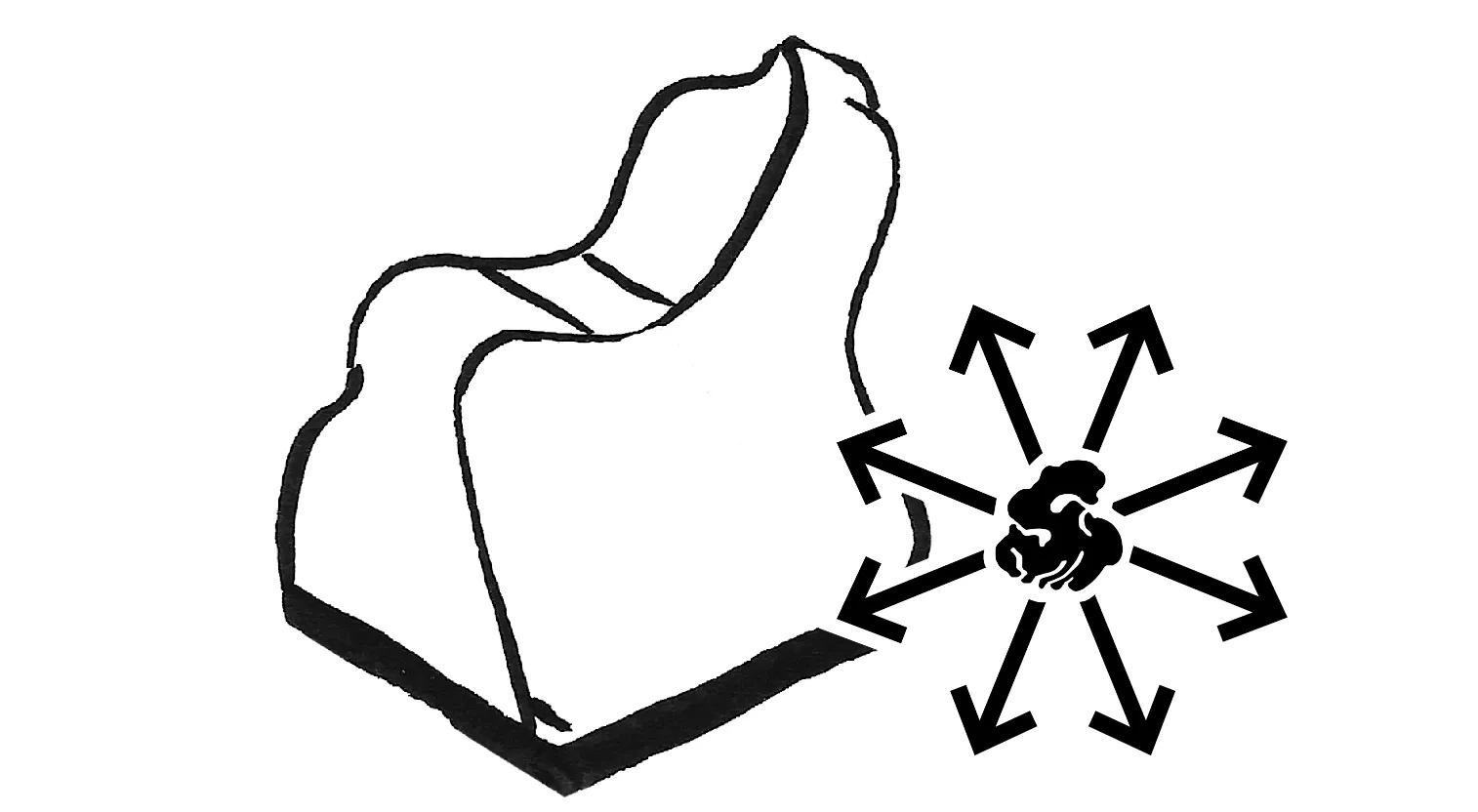

Below: The Cloak's basic movement

Taking: The Cloak fends all your opponent's fendable pieces and takes only the Lantern (extinguished).

Vulnerability: The Cloak can be fended by all pieces and is taken by the Lantern (burned) and when a blade ends its Blade Capture move (severed).

Special move: Feign

When the Cloak and the Self are adjacent to one another (orthogonally or diagonally) they can switch places as a double-move turn.

Below: The Cloak and the Self trade places by feign

Special move: Blade Capture

The Cloak can attack the Sword or Dagger without taking or fending it; instead, it sits atop the blade and keeps it pinned in one place.

The owner of the captured blade may not immediately free it. They must spend a later turn if they wish to remove the Cloak (which may also be done in concert with the Self's movement). The Cloak is then destroyed. However, if on some future turn the Cloak is still in play upon a captured blade, its owner may move it back off, releasing the blade and saving the Cloak.

Blade capture is an attack on the blade, thus it may contribute to disadvantage conditions for disarm. Disarming a captured blade fends the Cloak.

Your blade/s may not leap over your Cloak while it captures (because they cannot leap an opponent's piece).

You may not make a move with the Cloak that begins and ends with blade capture. For example, you can't jump your Cloak from your opponent's Sword to their Dagger, capturing back and forth turn after turn (or even one such move). Also, you may not make a double-move by stepping stone to leave and immediately recapture a blade.

While a blade is captured by the Cloak, neither the blade nor the Cloak can contribute disadvantage to the disarm of a separate armament.

Why can't I remove the Cloak with an attack from another piece? The timing of the imagined scene is like this: an attempt to free your blade momentarily fails (the point of the move), and then you remaneuver to sever or wrest away the cloak. There isn't a moment when you need to try and free it by other means, and you get more out of destroying it anyway. These are also simply the limitations of working with grid squares, abstract pieces, and sequential turns.

Below: The Sword captured by the black Cloak

Balance ...or Shadow*

The Balance is analogous to the bishop in chess. It moves one or more spaces along the diagonals, constrained by the edges of the board. The Balance, however, can leap over any piece in its path.

Below: Examples of the Balance's diagonal movements

Taking: The Balance fends all your opponent's fendable pieces and takes the Jutsu (transcended).

Vulnerability: The Balance can be fended by all pieces and taken by the Guard (bludgeoned).

Due to its pattern of movement, note that the Balance can only reach half the spaces on the board, like a black-square or white-square bishop in chess, unless placed alternately out of reserve or via the use of its special move, Shift.

Aspect: Control

The Balance in the Self's measure prevents an opponent's Jutsu from entering (by movement or attack), and entering the opponent's Jutsu-occupied measure with your Balance and Self fends their Jutsu.

This can be invoked in the moment in order to fend a sitting Jutsu or prevent its movement into a measure, but cannot be remembered and invoked on a turn later than when the relevant move occurred.

If the Jutsu attempts to attack or move into the measure where Control is active, the move is merely prevented. However, if playing by turn-penalty for untenable moves, the move is prevented and the turn skipped. If playing by piece-penalty, the Jutsu is fended and the turn skipped.

Special move: Shift

The Balance can shift to trade places with the Sword or Dagger anywhere on the board, assuming the blade piece's destination is within its normal constraints.

This move cannot be used in concert with the Self's movement, nor as the second in a double-move by engagement.

Below: The Balance and the Sword trade places by shift

* “Shadow” here is a counterfeit word implying a metaphysical “balance,” in the sense that a shadow is a reflection of the self.

Dagger

The Dagger is an additional reserve piece which can be put into play as a turn (as are all the pieces that follow). It moves like the Sword but cannot leap, and it is constrained to the same measure as the Self and one measure outside—no further extension from the engagements. If the Dagger is left outside of constraint to the Self, it can only move to a square back into constraint with the Self.

The Dagger cannot be used to execute disarmament unless you have lost your Sword.

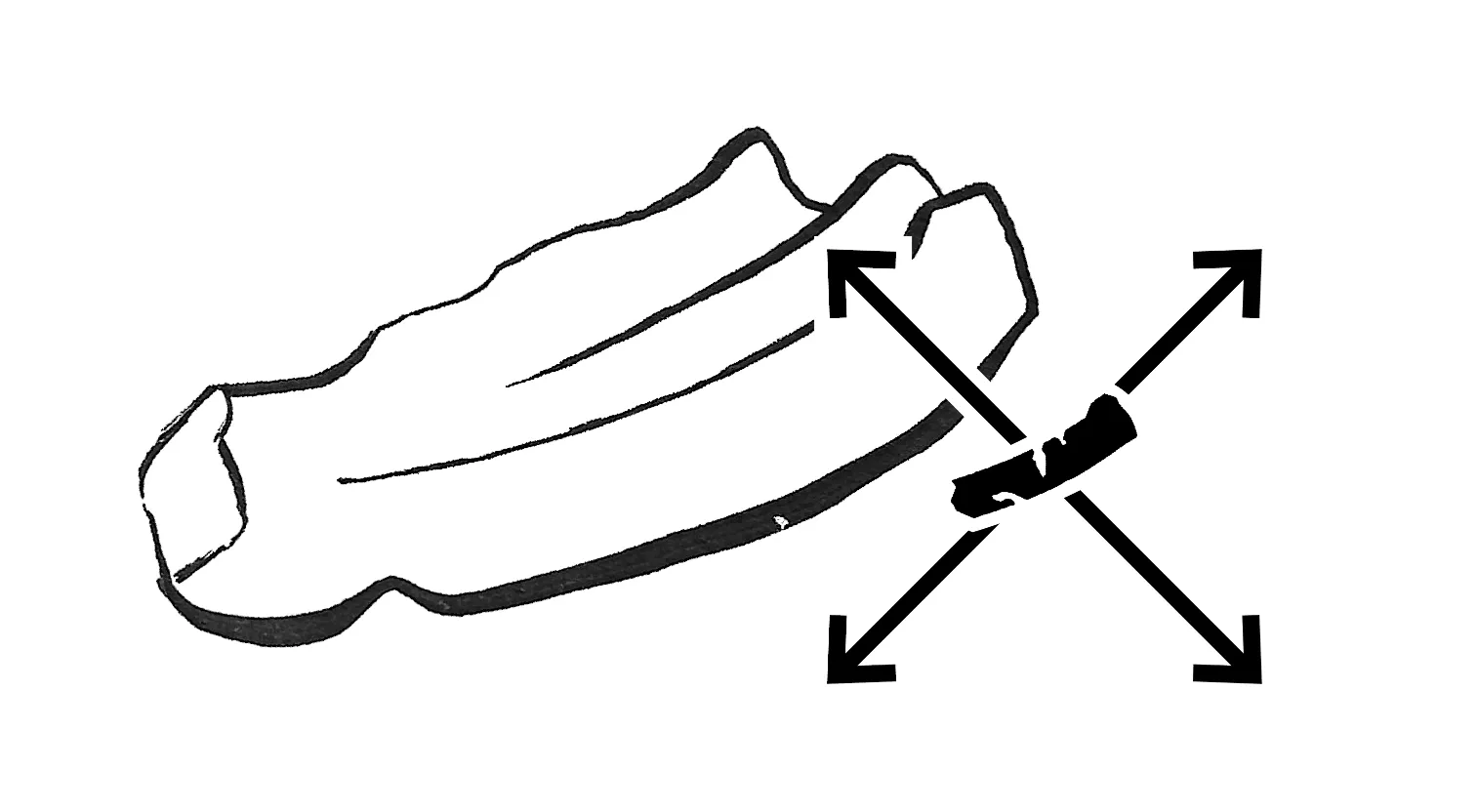

Below: An example of the Dagger's range and available movements.

Taking: Just as the Sword, the Dagger fends all your opponent's fendable pieces unless it can take as follows…

- Balance is never taken, only fended (shadow-stabbing).

- Lantern is always taken, directly (shattered).

- Cloak is only taken in counter-action, by cutting free from its special move (severed).

- Jutsu is taken indirectly, by fending Balance (shadow-stabbing).

- Engagements are only fended.

- Armaments — Sword, Guard, and Dagger — are taken only via conditions of disarmament.

- Self is taken directly, as checkmate.

- Ruin/Rien cannot be taken or fended.

Vulnerability: The Dagger cannot be fended, and can only be taken by the opposing player's Sword (or Dagger, if their Sword is lost) via disarm conditions.

When your Dagger is in play, as it is an armament, you may choose to move it instead of your Sword in concert with your Self piece.

Special moves: Cavazione & Opposition

The Dagger can make use of cavazione and opposition, the special moves of the Sword, but only against the opponent's Dagger.

Aspect: Persistence

If you lose your Sword, but you already have a Dagger in play, you may continue to fight. The Dagger gains the ability to execute disarmament in place of the Sword.

You cannot put your lost Sword back into play, and you cannot put your Dagger into play upon losing your Sword; it must be already active in order to prevent checkmate by disarmament of the Sword.

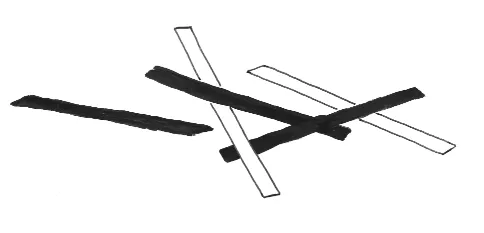

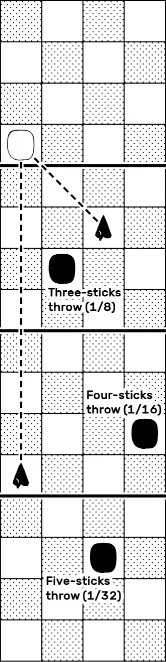

When the Dagger and the opponent's Self are aligned unobstructed by any piece other than engagements, the Dagger can be used for a long-range attack from any distance.

- Success on the attack is determined by chance. The standard method of rolling for this is with a set of five stick-dice. (These could be knucklebones, flat popsicle sticks with one side of each painted black, or square-sided sticks with two adjacent sides on each black, or two-sided round/flat Senet-style throwing sticks. …Or even just consecutive coin-flips. See alternate methods in the reference section.)

- The number of sticks thrown is three plus the number of measures between the two Selves. (At full starting distance, this is a one-in-32 chance of success. At close range, it's a one-in-four chance of success.)

- The attacker throws for their piece color, white or black.

- If Black's throw lands all black-side-up, for example, the attack is a success and constitutes checkmate by touch.

- If the attacker throws only one off-color, the attack misses but grants a short-success distraction effect which allows the throwing player to reposition their Self piece and the Sword anywhere on their side of the board and behind the opponent's Self's step, otherwise irrespective of movement and range constraints, without taking pieces (similar to the piece-repositioning effect of Obscurant Chaos).

You may use the Dagger Throw ability in concert with a Self move. You may also throw as the second in a double-move by stepping stones with the Dagger.

Below: Two examples of Dagger Throw attacks (dashed lines) and three positions with different odds of success (labeled Self pieces)

Guard ...or “Ward”

The Guard moves like a rook, one or more spaces orthogonally (in a step or line), or one square diagonally in any direction—these amount to the "Dragon King" piece movement from Shogi. However, its range is tightly constrained to the Self's measure and one step outside. If a Guard is left out of constraint to the Self, it can only move to a square back into constraint with the Self. It cannot leap over pieces.

Below: An example of the Guard's range and available movements.

Taking: The Guard fends all your opponent's fendable pieces and takes the Balance (bludgeoned).

Vulnerability: Cannot be fended, and is taken only by the Jutsu (subverted) and by the blades via disarm.

Aspect: Armament

When your Guard is in play, you may choose to move it instead of a blade in concert with your Self piece. It cannot be fended as other technicals can.

Although the Guard is categorized as a technical piece and is named after a defensive concept, it represents something wielded, something steel, and so is considered an armament.

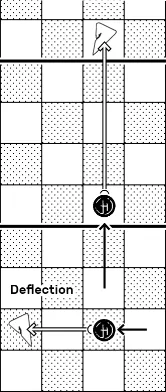

Special move: Deflection

The Guard is able to deflect an armament and push it away if there is at least one open square immediately behind the latter and as long as the Guard doesn't move outside its constraints.

The Guard takes the square of the blade it deflected. If this square is on your side of the board, the opponent's blade is pushed away until it crosses back onto their side, or until it is blocked (by a left or right edge of the board or another piece in the way). If the taken square is on the opponent's side of the board, deflection pushes the blade piece only one square. Deflection “backward” (toward your end of the board) only pushes the opponent's blade one sqare.

Blade deflection does not constitute a move by the deflected opponent, who then takes their normal turn.

This can be the second in a double-move by stepping-stone or a move in concert with the Self.

Below: The Guard deflects the Sword back across the center line; The Guard deflects the Sword sideways to the edge of the board.

Lantern

The Lantern is a strange piece. Its basic movement is diagonally and orthogonally, like a queen, but it can only move more than one space. Also, it is initially constrained to the Self's measure. When the Self moves out of that constraint, the Lantern moves by flailing either back into measure with the Self or one further, swinging like a pendulum.

The Lantern cannot jump over pieces except those in the adjacent measure it passes into or over when flailing. It can never jump over pieces in the same measure as where it starts a movement (see: “Flail” special move below for more in-depth description of this movement pattern).

Below: Example sequence of possible Lantern movements within its constraint to the Self, without flailing.

Taking: The Lantern fends all your opponent's fendable pieces and takes the Cloak (burned).

Vulnerability: The Lantern is fended by any piece, and is taken by the Cloak (extinguished) or by either blade (shattered).

Aspect: Pseudo-Armament

When your Lantern is in play, you may choose to move it instead of an armament in concert with your Self piece.

Note that although the Lantern isn't technically subject to disarm conditions, it is nevertheless destroyed by any attack from a blade.

Special move: Flail

When the Lantern is left out-of-constraint by the Self having moved away into another measure, it can move either back into-measure with the Self or one measure further in that direction, on the opposite side of the Self from where it started the move (as if swinging). Also, it can leap over any pieces in the next measure it passes into/over, like a flail whipping around obstacles.

The flailing Lantern can only leap over pieces in the next measure if its path isn't first obstructed by any pieces in the measure where it begins the move. (In fairy chess piece terms, this is like a slide-then-leap move. Think of it as requiring momentum to leap.)

When flailing, the Lantern may double-move by stepping stone to further complicate its potential movements, but only using an engagement square and destination square that share a measure.

Any Lantern move which terminates inside the Self's measure ends its state of flailing, precluding any stepping-stone move which involves a leap or leaving the measure again until a later turn, once flailing again.

The Lantern, when flailing (i.e. not in-measure with the Self) can never make a move which begins the turn and ends the turn in that same measure.

As it is a technical piece, a Lantern poised in a direct attack by flailing can contribute to disadvantagement for disarm.

Thus, for the Lantern, constraint to the Self inverts itself and provides an opportunity to attack much further and more dynamically than was possible a moment earlier, potentially catching your opponent's center by surprise. Upon the Self's advance of a measure, the Lantern suddenly becomes able to move upwards of eleven spaces straight ahead. If the Self takes yet another measure forward before the Lantern is pulled along (like the steps of shot put thrower), the Lantern could conceivably travel up to 15 spaces forward in one move, the full length of the board.

By this mechanic, the Lantern begins the game with a very limited set of short, awkward moves but can join the endgame with the longest moves made by any piece on the board. However, it can also become tangled and trapped among pieces.

Below: One example of a flailing Lantern move. Many more complex variations are possible.

Aspect: Glare

The Lantern emits light. When it aligns with the opponent's Self (orthogonally or diagonally) unobstructed by a Guard, Cloak or your own Self, the opponent's Jutsu is fended. This can be declared at any point on your own turn when the position allows, and does not constitute a move for the purposes of move-count. However, using glare ends your turn.

The opponent affected by glare may not immediately replace the Jutsu on their next turn.

Glare conditions while the opponent's Jutsu is in reserve may prevent its placement until glare is broken. You may also be invoke glare to prevent a Dagger Throw.

The Lantern's movements resemble a swinging pendulum. While it is inside the Self's measure, as a side-effect of its limitations, it cannot move in the same direction twice, as if swinging to and fro. Only able to go two or three squares at a time, it moves as if carrying momentum and thus unable make short, precise adjustments. You could also imagine that it needs that same momentum to take another piece without simply bouncing off). In a cluttered measure, its movements become severely entangled and restricted.

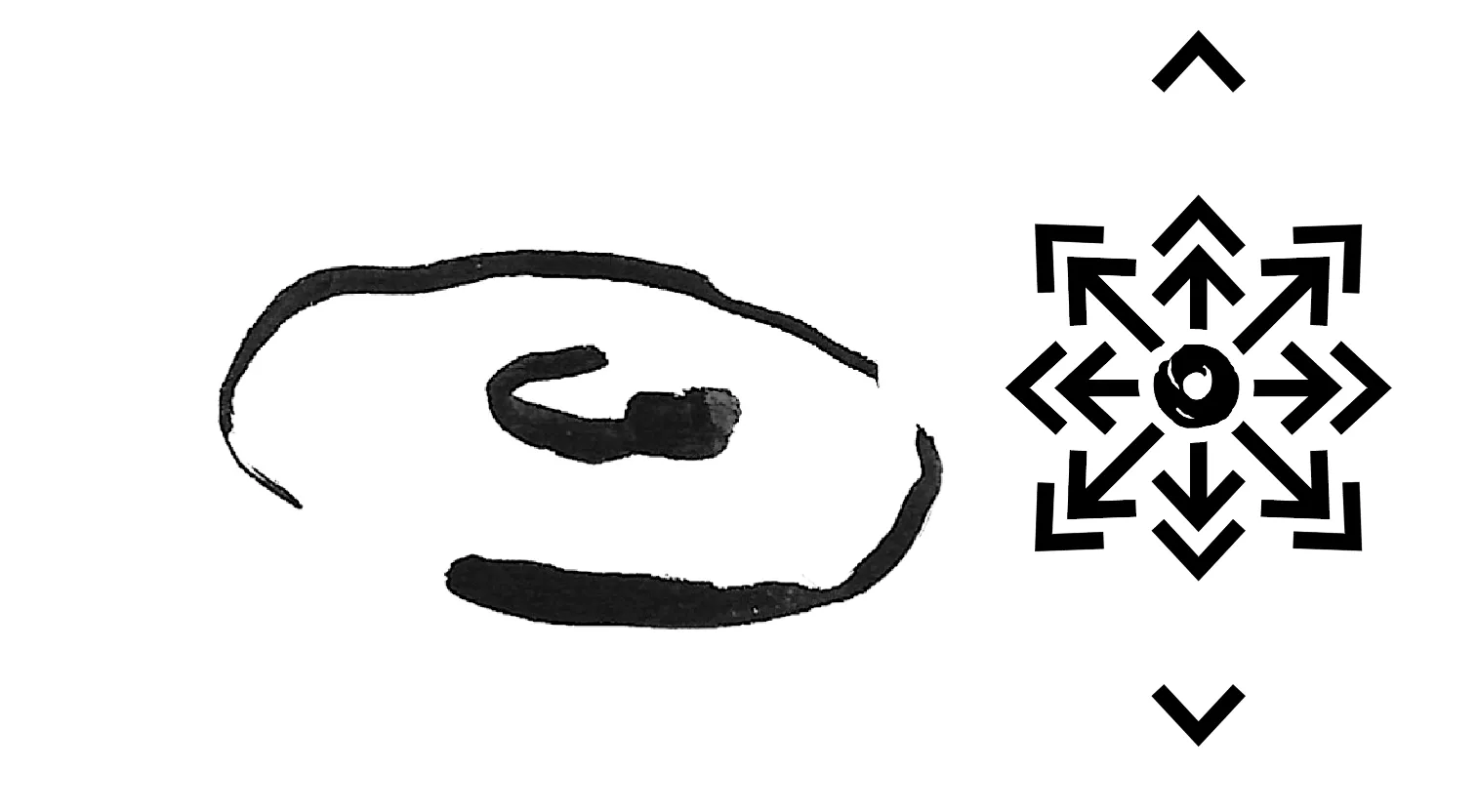

Jutsu

This piece moves one or two squares (leaping) in any direction or blinks to the corresponding square in any measure.

Below: examples of the Jutsu's movement

Taking: The Jutsu fends all your opponent's fendable pieces and takes the Guard (subverted) as well as the opponent's Jutsu and itself simultaneously in negation.

Vulnerability: The Jutsu is fended by any piece and taken by the Balance (transcended), by the Jutsu (negated), or via an opposing blade fending the Balance (shadow-stabbing).

Aspect: Presence

Your Jutsu's presence in the same measure as your Self piece prevents your opponent from placing any pieces from reserve into that measure.

This can be invoked in the moment in order to call piece placement untenable, but cannot be remembered and invoked at a later time to dispute the previous piece placement.

When your Jutsu occupies the same measure or diagonal as a piece you wish to target, and your Sword (or blade) sees the targeted piece, (either directly or by double-move) you can declare an intention of a specified attack on that target piece in advance. When you make the move on the next turn, you enact the intention to take (or fend) that piece without moving into its square (an attack sometimes called a “strike” in chess variants) …unless your opponent moves the target piece or removes your Jutsu from the board on their intervening move. When an intention is enacted, the Jutsu is put into reserve.

Declaring intention ends your turn.

Enacting intention is a move and requires the use of a turn (unlike declaring), but may be done along with a move in concert by the Self and/or a double-move by the Sword to position for the enactment (see final bullet point below).

Intention allows a blade to take or fend a piece one step beyond its normal constraints when it is adjacent to its target. The attacking blade otherwise cannot enact an intention outside its range constraint.

However, you may bluff an intention of any describable move, even if it is untenable, perhaps in order to draw a desired reaction from your opponent.

You cannot meta-move and declare intention on the same turn.

- You can declare intention on the same turn as moving the Jutsu into the necessary position.

- Declaring intention and passing with no move made on the board counts as a pass (for the purposes of passing rules).

- An intention can only be enacted on the immediately following turn, but declaring an intention does not preclude the possibility of changing your mind and simply taking the target piece by a normal move on that turn or a later turn.

- If you disregard your prior intention by making any other move, the intention is forfeit and must be re-declared in order to enact it.

- If you delay declaring intention or didn't think it through before making a move, your opponent can cut you off and make their move before you declare intention.

- For over-the-board play, you must start declaring intention while holding the piece with which you're making the last move of your turn. Somewhere between picking up the piece and before letting go of it, you begin to say “Intention…” and then describe the intended move (of course not necessarily with the piece you just moved, which needn't be related. If you're using time controls, you would hit the clock after finishing that declaration.

- A move identified by declaring intention can be the second part of a double-move, such as a move in concert with the Self.

- If the Sword would use an engagement double-move in order to reach the attacked piece in the movement declared by intention, when enacted, the engagement is removed and the Sword moves to that space before taking the target piece by strike.

Below: An example where Jutsu (in either position) and Sword declare and enact intention.

This is like a feint in fencing. You telegraph intention of a valid threat. If the opponent doesn't defend against it, or can't, you can follow through with a quick cut and otherwise pretty much maintain your blade position, controlling a line. If they do defend or evade but also open a vulnerability or ignore a threat you have planned, you can abandon your stated intention and make an even deadlier attack.

OPTIONAL PIECE:

Ruin/Rien

The Ruin or Rien is an inert blocking piece which has three defining characteristics:

- Moves pathlessly to any open square within the Self's measure or one measure outside but cannot move within the opponent's Self measure.

- Cannot take or fend any piece.

- Cannot be taken or fended.

Aspect: Floating Ruin

The Ruin can be placed from reserve anywhere in its movement range, ignoring the constraint of the piece-placement area.

Using the Ruin in a game has two specific effects. Most obviously, it offers quick, solidly blocking defense against straight-line direct attacks. However, it may ultimately prove useless against more complex attacks, while also expending turns in order to place and reposition the piece.

Aside from these calculations, in general it adds another element of complexity to the shape of the fight at the center of the board.

Note that the Ruin doesn't quite fit into any category of piece-type. It's most like a technical piece, but its inert role among other pieces disqualifies it from most everything of what the rules have to say about technical pieces.

About Nothing

The origin of this piece's name, or names, is another bit of artificial etymology like that of the Balance/Shadow. The piece was first conceived as representing shifting forces of orbit and repulsion involved in a sword fight—intangible yet gravitational, undeniable—which dictate what path you can or can't take at any given moment. These are abstract objects and mechanisms, not “real” ones, focal points in time and space created by the interaction between two consciousnesses. “Rien” is an unrelated French word from fencing terminology, meaning simply “nothing” (as in “nothing done”). As a null element on the board representing forces in empty space, this piece has qualities of nothing yet also qualities of real, obstructive physicality. Figuratively, it is like a tree or column, some obstacle of strategic cover found by maneuvering through a real environment. Quite the opposite of “nothing.” Language can be funny; Imagine a borrowed word that isn't understood (see: rukh/rook), misheard or reinterpreted, re-justified via malapropism. “Ruin” ...kind of sounds like rien? Ruins of things like walls and columns. Empires fall and turn to rubble; solid structure becomes nothing. Trees grow up between the rocks. Sword, destroyed by sword, rusts away.

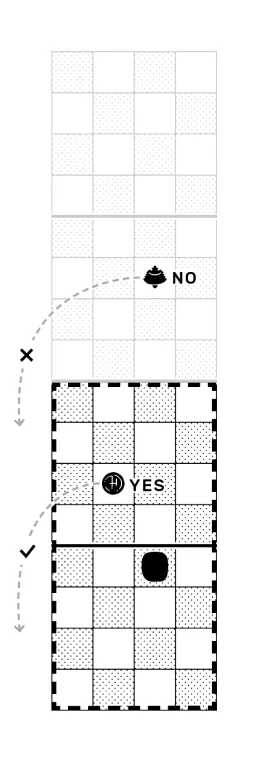

Placing Pieces from Reserve

Your pieces in reserve can be placed on the board as a turn. Pieces that have been taken / lost to discard cannot be placed, and you can never place a piece as one part of a double-move.

Pieces can be placed only on empty squares adjacent to the Self, and range constraints still apply.

Note that the special aspect of the Jutsu prevents piece placement in a measure, and similarly the aspect of the Balance presence in a measure prevents the Jutsu specifically from entering or being placed there.

Placing a Lantern or Jutsu may allow you to use Glare or declare an Intention. These wouldn't be double-moves, per se, because you've only actually moved one piece (see Double-Moves).

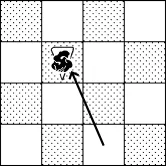

Below: Black's piece-placement area is within the dashed line, on any empty square adjacent to the Self.

Withdrawing Pieces

Players may withdraw their own pieces into reserve only from their own side of the board, excluding of course the Self piece and the Sword, as well as the Dagger if it is one's only remaining blade (unless you want to resign dramatically).

Below: Black may not withdraw the Lantern, which is on the opposing side of the board, but they can withdraw the Guard..

Disarm

The Sword takes opposing armaments via disarm conditions. If the Sword has been lost, the Dagger is used to execute disarmament. Disarm conditions exist when either…

A. The disarmed piece is overextended in a measure outside its range constraints.

- If this can be done instead of simply calling out the opponent's untenable move outside constraints, that is of course competetively preferable. In a more friendly game, maybe not so. It depends how much you want to punish mistakes.

B. The disarmed piece is disadvantaged under attack from a blade and direct attack from a technical piece simultaneously:

- For example, if your opponent's Sword occupies a square within the paths of both your Balance and Sword at once, you may disarm their Sword with an attack by your Sword.

- The attacking blade makes the move to take the disadvantaged armament. The other piece involved in the attack stays put. However...

- A technical piece supporting for disadvantage in a disarming attack cannot do so via speculative double-move (by engagement or any other means); it must directly “see” the disarmed piece. The attacking blade which performs the disarm may do so by double-move.

- This means the players must be alert to all threats, even those of lesser pieces to which the Sword is ordinarily invulnerable.

- The Balance's aspect of “Control” may be invoked to prevent a disarmament which would rely on the Jutsu attacking into a controlled measure.

- Ending the device Hirakamae provides an opportunity to move two pieces unrelated by the typical double-move mechanics, which could make for sudden disarming attacks.

Below: White's Sword is both overextended and triply disadvantaged (though just one of these would suffice for a disarm). Black's Sword can use the engagement's stepping-stone facilitation to double-move and disarm for checkmate.

Your attacking blade should, of course, stay within range constraints while performing the disarm. Failure to observe this could result in simply having the move called untenable and reverted, losing the piece by penalty, or even the opponent opting to disarm you in return. It is important to understand the concepts of “playing with sand” and untenable moves in order to navigate these ambiguities.

If the disarmed player has no blade left on the board, disarmament constitutes checkmate with no possibility of double-checkmate in return.

Double-Moves

Each player can only make a maximum of one or two moves total in a turn. A double-move can be made via only one of the many methods of double-move, even if the conditions for more than one method are available.

At this experimental stage, it may help to exhaustively enumerate these methods and define our terms to prevent loopholes for triple, x-tuple, or infinite chains of moves. You can reference this section if there is ever any ambiguity in that regard.

A move occurs when one of your own pieces enters a square or leaves a square, or does both in one movement, takes or fends a piece, or uses a special action on another piece. A “move” is more precisely defined as any discrete action originating from one of your pieces in a square on the board in relation to another piece or square. Examples:

- Moving to an empty square is a move.

- Placing a piece from reserve is a move.

- Withdrawing a piece is a move.

- Taking or fending an opponent's piece is a move.

- Stepping-stone onto one of your own engagements (without take the extra move it allows) is a move.

- Enacting a previously declared intention is a move.

- The device Shadow-Stabbing is a move (not a double-move; the blade is your one piece that moves to perform shadow-stabbing, even though two pieces are taken).

- The cast-piece devices are each a single move. For the cast Cloak, Obscurant Chaos, the resulting rearrangement-moves disregard these rules because they consist of special repositioning irrespective of the pieces' normal movements; it's all one move, but incidentally it can never be linked to further moves on one turn.

- Similarly, the piece repositioning offered by the distraction effect of the Dagger Throw doesn't count as additional moves, because the pieces are repositioned irrespective of their normal movements. Thus, if you double-move to make a Dagger throw and roll a short-success, repositioning with the distraction effect is allowed before ending your turn.

- Glare is the exception to the above definition of a move; it is thought of as instantaneous, allowing revealed-glare attacks.

A “double-move” refers to both or the second move in a turn where a player makes two moves. Double-moves must be linked by the preconditions of an allowed type of double-move. Examples:

- Using the engagement's facilitation as a stepping stone for a second move by the same piece is a double-move.

- Stepping-stone onto your own engagement and then using a special move now available to the same piece (like Dagger Throw, Cavazione, Opposition, or Blade Capture) is a double-move.

- Moving an armament in concert with the Self is a double-move.

- Moving an armament in concert with the Self after the Self step-stones onto a square occupied by one of your engagements is a double-move (assuming the Self only moves once).

- The special ability Shift is a double-move (it moves two of your own pieces).

- The special ability Feign is a double-move (it moves two of your own pieces).

- Use of the Fire Dance cast-square is a double-move (grants another move to a piece that has landed on it).

- Ending Hirakamae offers a double-move, consisting of two moves by one piece, or one move each by any two different pieces.

Not a double-move:

- Movement or withdrawal of a piece to reveal and invoke Glare is not technically a double-move, because Glare does not constitute a move, but it is allowed and does of course end your turn.

Note that you can never use a special ability involving two of your own pieces as the second move in a double-move, because the special ability isn't one move; it's a double-move.

Your own engagements removed from the board for double-moves do not add to the move count, just as the opponent's pieces taken do not count.

Put more loosely in entirely different terms: To perform a double-move, you may physically touch-move square-to-square either one piece twice or no more than two of your own pieces once each on your own turn (not counting removed engagements).

Immaterial Actions

Meta-moves do not actually count as “moves” (the piece does not yet occupy real space on the board), and neither does declaring intention (because no move is made until enacted). Similarly, the special ability Glare does not count as a move, because it isn't always necessary to move a piece in order to use it (it consists of light and is theoretically instantaneous). In fact, making only a meta-move, only declaring intention, or only glare technically each amount to a pass, because you've made no square-to-square move with any of your own pieces.

To reiterate and gather here some relevant rules:

- Declaring intention ends your turn.

- Conversely, a meta-move must be made before the normal moves of your turn.

- Using the special ability Glare ends your turn.

- You cannot meta-move and declare intention on the same turn.

- Declaring intention and making a meta-move do not count toward the double-move count.

- Declare-intention-and-pass counts as a pass

- Meta-move-and-pass counts as a pass

- Glare-and-pass (with no move preceding glare) counts as a pass.

So, a really complex turn could conceivably go as follows: Meta- move the free engagement; Self lunges forward; Lantern flails forward to take Cloak, revealing Glare to fend the Jutsu. (Would be notated like: aw SY7 LtZ8 LfJ~)

To indicate that you're finished making a chain of special and optional meta-moves, etc., you may wish to say “your move” or “…and to you,” or “à toi” if you're fancy, although the use of a turn-counter obviates the need for this. (See also: Passing and Custom Rules & Extra)

A Note on Form

Double-moves should be made without pause, after having fully thought them through. Or, you can begin to move a piece and hold onto it while thinking through the next move (as if observing the touch-move rule in chess) and make the additional move with the same hand (see Concert of Self). Observing good form here prevents moments where you might suddenly decide you want to make a double-move at the same moment your opponent reaches to make their own move, assuming your turn had ended. Of course, in a friendly game, this matters much less, and furthermore it is never really against the rules to go ahead and make a double-move that you previously declined unless you explicitly stated that your turn was finished.

Passing

A player may choose to pass a turn, but if the opponent then also passes, the first player who passed must now make a move on the board. In other words, a maximum two passes can occur consecutively.

This effectively means you can pass unless the other player denies it. When your opponent passes, you have to decide whether it's worth more to you to A) accept their pass and make an extra move in tempo ahead of them, or B) reject the pass and force them to move, perhaps even zugzwang (when they would prefer not to move). You can imagine it as if one fencer has stood still, but the other makes an instigating movement toward them and forces a reaction.

The three immaterial actions (meta-move, intention, and glare) will not suffice to respond to this forced move.

Note that colloquially saying “…and pass” after making a move with the Self or otherwise declining to make a double-move (e.g. upon stepping stone by engagement) is distinct from actually passing a turn, and may be misinterpreted. It is preferable to instead say “your move” or “…and to you.”

Is any of this necessary?

There are usually plenty of pieces with which you can make a “waiting move,” or pieces to be placed from reserve, or meta-moves which are all comparable to a pass. Chess, likewise, already allows forms of crypto-passing in most of the early to middle game anyway, what with waiting moves and repetition. Nevertheless, for the sake of adding another sandbox item, here is real passing. It is still important to avoid the stalemate eventualities of extended pass-repetition and any other potentially bugged situations arising from badly defined rules. The implications and intersections of double-moves, passing, and immaterial moves have all made it very difficult to discuss any of this succinctly. Time will tell.

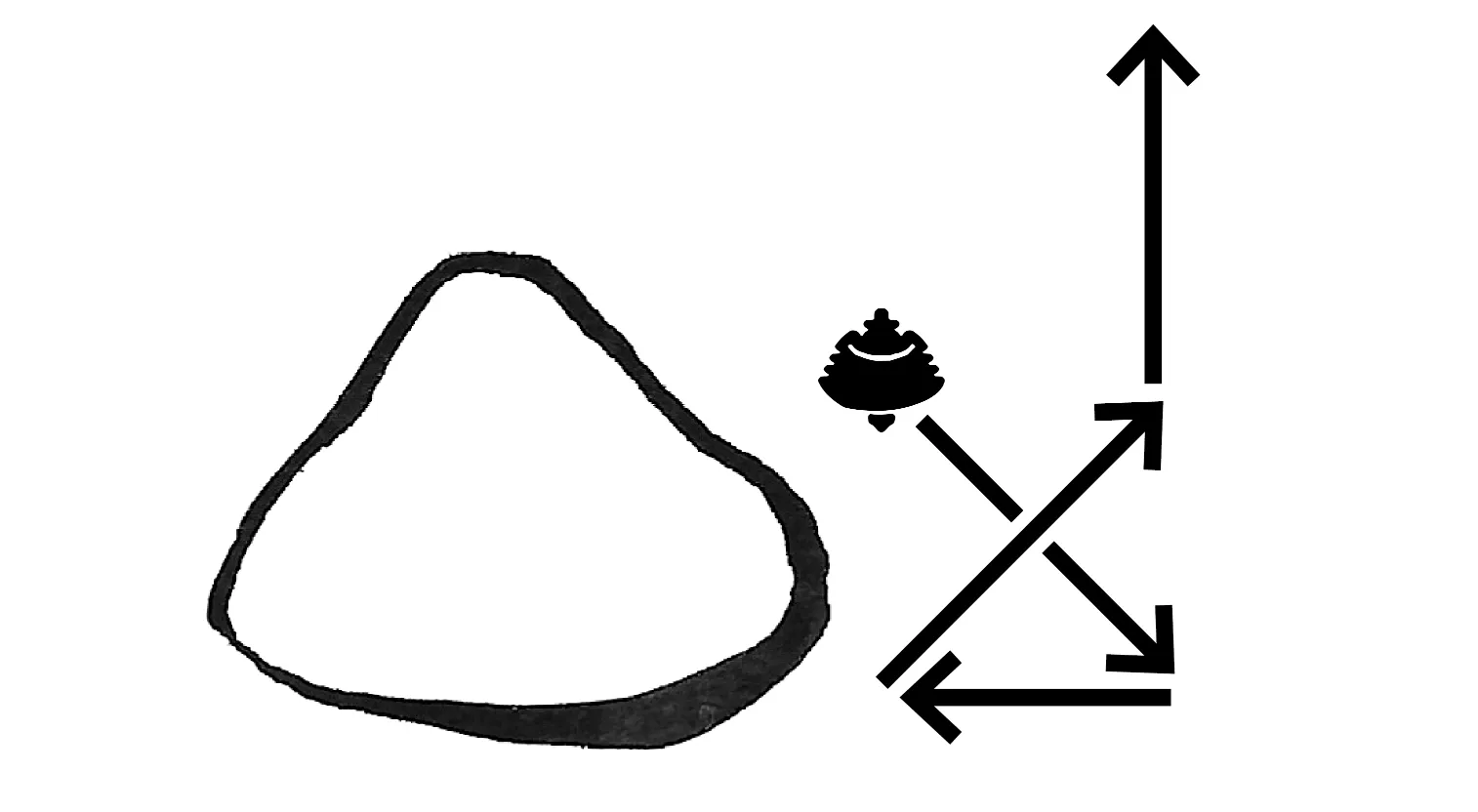

Devices of Art & Mysticism

The devices consist of a handful of special moves created by interactions between two or more pieces with an effect on a separate piece or on the rules of the game itself.

Shadow-Stabbing: When your opponent's Balance is on your side of the board, fending it with a blade takes the Jutsu regardless of whether it is on the board or in reserve. The Balance, fended, goes into the opponent's reserve. This is a common part of the mechanics of fighting pieces, but since it involves more than just one piece taking another, it belongs in the category of devices and neatly exemplifies them.

Hirakamae Stance: This position consists of one's only blade piece beside the Self in a step, or both blades on either side of the Self, in an otherwise empty measure. The player can pass indefinitely without risking a draw and the adversary may not pass–they must continue making moves between these passes or resign. A move made by the enstanced player ends hirakamae and may be a double-move made with any one or two unrelated pieces (one move by each piece), after which normal play resumes. Hirakamae may only be used once per game.

…unsure if this would be most appropriately called “hirakamae stance,” “hira no kamae” or “Hira ichimonji no kamae.” As seen in a duel scene in the excellent anti-samurai film ‘Seppuku’ (切腹, released in English as ‘Harakiri’ — dir. Kobayashi Masaki, 1962)

Death Spell: In a formal game, if the player checkmated by touch immediately follows not with double-checkmate but rather with the negation of Jutsu-takes-Jutsu, they still lose, but the ceremonial prize is upended: the losing player takes the winning player's token.

Cast Piece: Into a rare empty measure between the two players' Self pieces, excluding the allowed presence of the free engagement, one may throw their own Lantern, Cloak, or Dagger piece to initiate an effect. This move is made irrespective of normal movement or range constraints and is performed by literally tossing the piece down onto the board (a short distance, like the roll of a die). The piece may be used for this casting by picking it up off the board or from reserve, but never from discard. Casting Lantern or Dagger in concert with a Self move is allowed.

If it is unclear which square the piece landed within or leans most toward, the caster's opponent adjusts it to a square that it touches. If the piece falls outside the empty measure, it is lost with no effect. (In the case of a piece landing dubiously on the outside edge of a measure, an impartial arbiter or coin-flip may be needed to determine whether it's in or out.)

In the square where the cast piece landed, the players notate or commit to memory a cast-square which can be recalled for use later in the game. The cast piece is then discarded.

Unless the empty measure becomes occupied by a caster's piece(s) on their turn (as is possible via the immediate effects of a cast Cloak), the opponent, on the following turn, may still use the empty measure to cast their own piece. For example, if one player casts their Lantern, it is not uncommon that the other would likewise cast theirs to match.

The cast-piece devices are as follows:

Cast Lantern – Fire Dance: Any one of the caster's pieces which enter the cast-square may make a double-move from that space as if by stepping stone, even in conjunction with taking an opponent's piece on that square. The square may be visibly marked with a flat tile or small token, if you wish. Use of the cast-square is voluntary and unlimited.

Cast Cloak – Obscurant Chaos: Immediately upon casting, the caster is allowed to completely reposition their Self piece and one blade anywhere on their side of the board and behind the step the cast Cloak landed in, otherwise irrespective of movement and range constraints—but without taking pieces. On future turns, any one of the opponent's technical pieces which enter the cast-square can be immediately lost to discard if the caster invokes it (including if the opponent has just taken a piece or placed their own piece on that square, or even interrupting a double-move in process) at which time the caster may once again completely reposition their Self and a blade piece on their side of the board, behind the cast square, but this time able to take pieces via the repositioning. However, this rearrangement of criticals counts as the caster's turn; it might be performed only with the Self or opted out of entirely to instead make a normal move or double-move, respectively. The square can remain unmarked for the added drama of a trap. Invoking the square is voluntary, and can be withheld for as long as the caster wishes. After one use, the cast-square is spent and cannot be used again.